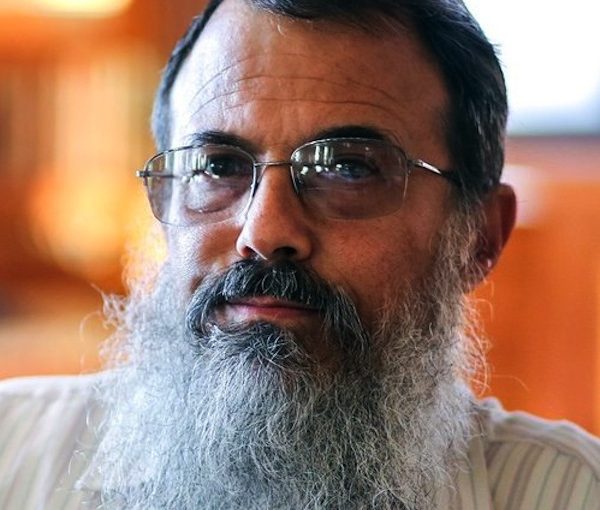

On May 30, the Global Reporting Centre’s Peter Klein will give the talk Disinformation and Democracy. (photo from VST)

Emmy Award-winning journalist Peter Klein will be the keynote speaker at this year’s Making Meaning in a Time of Media Polarization conference, organized by the Vancouver School of Theology (VST). Klein’s talk on the evening of May 30 – titled Disinformation and Democracy – is free and open to the public.

Klein, a professor at the University of British Columbia School of Journalism, Writing and Media, also heads the Global Reporting Centre, an independent news organization based at UBC that focuses on innovating global journalism. His lecture will explore the role that disinformation plays in both confusing the public and in undermining journalism.

“Open information is central to democracy,” said Klein. “There is no open society without open dialogue. In the past, the challenge was simply to restrict governments from curtailing the media. That was a challenge in itself, but, today, there are so many forces of propaganda and disinformation, many much more subtle than dictators arresting journalists.”

The origins of disinformation go back a long way, Klein noted. He referred to a Jan. 24, 2018, message on World Communications Day from Pope Francis who spoke of the “crafty serpent” in the Book of Genesis that created “fake news” to lure Adam and Even to “original sin.”

Klein will focus his talk on more contemporary efforts to lead people astray – from Germany’s Hitler to the Russian newspaper Pravda to Iraq’s Saddam Hussein. He will first look at disinformation from a North American context, then provide several international examples.

The Global Reporting Centre recently competed a study on disinformation attacks on journalists, or what he refers to as a “special subset of disinformation.”

“Attacking the messenger is an old trick that people in power have traditionally used, but social media has made it so much easier to undermine the authority of journalists,” said Klein, who has served as a producer for 60 Minutes, created video projects for the New York Times and written columns for the Globe and Mail, among other publications.

“Publish a critical story about a politician or business leader, and there’s a chance they or their supporters will come after you any way they can,” said Klein. “What we found in our study is that those wanting to undermine media do so by attacking on basis of race, gender and a number of other factors, which vary geographically.”

Though social media is what Klein calls “the pointy end of the stick,” mainstream media has, sometimes through disinformation, become polarized, too, he said. The Dominion Voting Systems case against Fox News, ending in April when the network paid a $787 million US settlement, is a clear example. Fox had falsely claimed that Dominion manipulated the results of the 2020 American presidential election.

“Fox had to pay for this, but they’re still standing, and I don’t necessarily see much change at the network,” Klein said.

The latter part of Klein’s talk will examine ways to combat disinformation. A key element of lessening the problem comes down to “public sophistication,” said Klein.

“We’re awash in fake news, not just political but calls to your cellphone that the RCMP is going to arrest you because of unpaid taxes, ads for incredible deals on household goods that just need a small deposit to hold the item, and the classic Nigerian prince scheme. I think we’re getting better at spotting that kind of fake information, although people still fall for it on a regular basis – including me recently, when looking for a deep freezer. As the public gets more sophisticated, so do the scammers.”

The same holds true for disinformation, according to Klein, and people need to improve their ability to identify falsehoods. He spoke about the visit a few years ago to the Global Reporting Centre by a journalist who exposed that torture was being committed by Iraqi special forces fighting ISIS. Following the visit, an Iraqi graduate student arrived at Klein’s office and presented a video that portrayed the journalist as a fabulist and a torturer himself.

“It turned out this video was part of a disinformation campaign in Iraq meant to undermine his embarrassing reporting, but she fell for it. We’re all susceptible, but if we can be better educated about disinformation and better equipped to spot it, we have a chance to combat it,” Klein said.

“In many ways, we’re more powerful than those who are combating traditional heavy-handed censorship and attacks on media. My parents fled Soviet-controlled Hungary, where public dialogue that was not in line with the state narrative could get you tossed in jail. We have the agency to combat it,” he said.

Making Meaning in a Time of Media Polarization, which will be held May 30-June 1, will be VST’s eighth annual inter-religious conference on public life. Its participants will seek answers on how spiritual and religious leaders might proceed at a time when social media, politicians and some news organizations sow polarization and cultivate outrage.

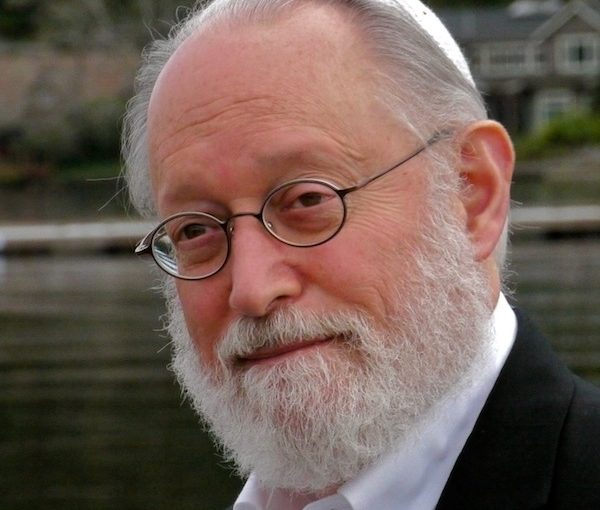

“Under COVID restrictions, our society’s stress points started to crack. We saw bad actors use media and social media to divide people, and we saw innocent, well-meaning people get drawn in,” said Rabbi Laura Duhan-Kaplan, director of Inter-Religious Studies and professor of Jewish studies at VST, who is the conference director.

“Ideally, in spiritual communities, people learn how to live a meaningful life with others. So, we started to think about how religious communities might respond to a crisis in public discourse,” she said. “We designed a conference where media experts can help us understand the crisis, and religious teachers can help us respond.”

To register for Klein’s talk – which will take place at Epiphany Chapel in-person, as well as online – visit vst.edu/inter-religious-studies-program/conference.

Sam Margolis has written for the Globe and Mail, the National Post, UPI and MSNBC.