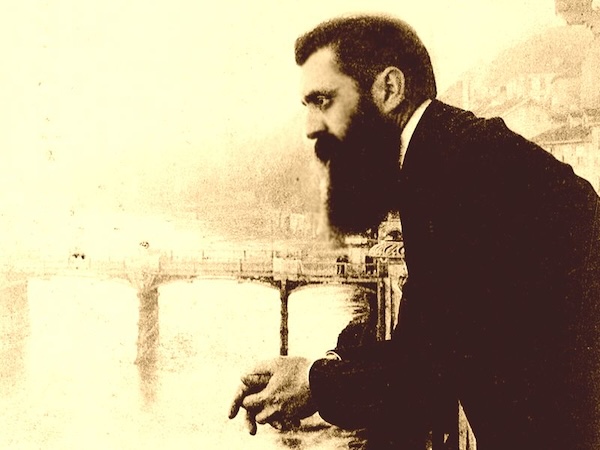

Theodor Herzl, during the First Zionist Congress, in Basel, Switzerland, 1897. (photo from mfa.gov.il)

Sometime before 1223, the first bridge spanning the Rhine River at Basel was constructed, funded through a loan to the town’s bishop by a Jewish moneylender. The bridge was a significant factor in the development of trade in the strategically located city, which is in northern Switzerland, near what are now the German and French borders.

The bridge lasted almost 800 years and was replaced between 1903 and 1905. There may be only one photograph in existence in which the original bridge can be seen – a photograph with another very significant Jewish connection. It is believed that the only place one can see the original Middle Bridge, or Mittlere Rheinbrücke, is in the famous shot of Theodor Herzl in a moment of contemplation outside the First Zionist Congress in 1897.

The bridge provides a sort of bookend to the Jewish story in Switzerland. While the bridge stood eight centuries, the history of Jews in Switzerland proved far less stable than the stone Mittlere Rheinbrücke.

Switzerland has a rightful reputation for natural magnificence – rolling green meadows, massive snowcapped mountains, glacial streams and rivers – as well as political stability and neutrality that have made it home to a host of international nongovernmental organizations and United Nations agencies. The prevalence of cheese and chocolate also give it a delicious reputation. History is not so agreeable.

Some of that history is told in Basel’s small but impressive Jewish Museum of Switzerland. When the institution opened in 1966, it was the first new Jewish museum in the German-speaking world since the Holocaust.

Basel itself holds a special place in Jewish history – for better and for far worse. Herzl, credited as the founder of political Zionism, was not one for false modesty. After his debut as convenor of the 1897 conference, he declared: “At Basel, I created the Jewish state. In five years, perhaps, and certainly in 50, everyone will see it.”

Herzl himself did not see it. He died in 1904. But, indeed, 50 years on, the United Nations passed the Partition Resolution and, a year after that, the state of Israel was created.

There are probably only about 1,000 Jews in Basel – there are around 20,000 in all of Switzerland – yet Basel stands out not only as the birthplace of the modern Zionist movement and home to the national museum of Jewish life and culture, but also has hosted the Zionist Congress 10 times, more than any other place.

Sadly, Basel is also on the Jewish historical map for far less rosy reasons. In 1349, an estimated 600 Jews were burned at the stake in Basel and 140 children were forcibly converted. This was just part of a series of pogroms in the 12th and 13th centuries across Switzerland, some based on blood libels or motivated by allegations of well poisonings at the time of the Black Plague.

Switzerland may have a reputation as being exceptional in Europe – neutral in foreign relations, and not a part of the European Union or most other multilateral bodies – but human-made borders and the majestic Alps seem to have done little to protect Swiss Jews from the horrors that have befallen coreligionists elsewhere on the continent across centuries.

As in other places, Swiss Jews were limited by law as to the professions they could pursue. A range of deliberately demeaning regulations were in place, including homes built with separate doors for Jews to enter. Jews were forced to pay what amounted to protection money to authorities.

Early in the 17th century, almost all Jews were expelled from Switzerland. Physicians were a professional exception and Jews were allowed to remain in just two villages.

After Napoleon invaded Switzerland, a series of political reforms began, some better and some worse for Jews.

Jews were formally permitted to settle anywhere in Switzerland after a referendum in 1866 resulted in a slight majority of Swiss endorsing equal rights for Jews. (The Swiss have a mania for referendums, even on issues of basic human rights.)

Migrants then came from middle and eastern Europe, especially after pogroms in Russia in the 1880s. More came from Germany after Hitler came to power, in 1933, but Switzerland, like the rest of the world, eventually slammed the doors shut, in 1938.

Swiss banks, with their uniquely secretive policies that protect the illegal and immoral, have been forced to reconcile, to an extent, with their complicity with the Nazis, as well as their profiteering from the assets of Jews who, because of the Holocaust, never reclaimed assets they had deposited for safekeeping as turmoil roiled their homelands.

Seemingly an oasis of stability and reason in a continent aflame in fascism, Switzerland nevertheless was steadfastly determined to prevent Jews from finding haven there. After the Anschluss, when Hitler’s army invaded and absorbed Austria, Jews from that country desperately tried to enter Switzerland, but mostly were met with rejection. Likewise, after the Nazis swamped France and the Low Countries, refugees from those places were similarly spurned.

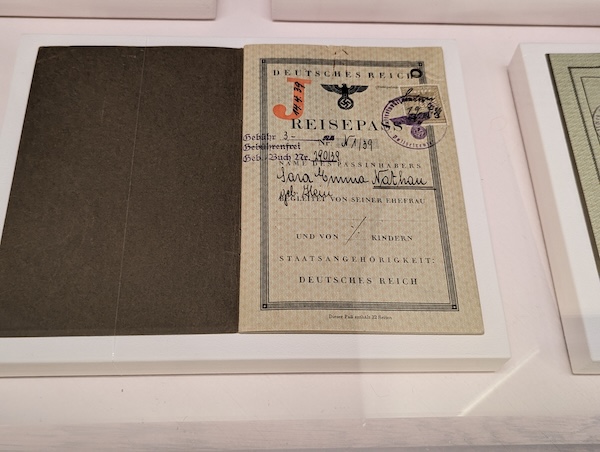

In all, about 23,000 Jews were admitted to Switzerland – but only as a country of transit. The Swiss authorities even prevailed upon the Third Reich – successfully – to stamp German passports issued to Jews with an unmistakable scarlet letter “J” to make it easier to identify and reject potential Jewish border-crossers.

In the 1990s, as Swiss actions during the Second World War and the Holocaust were the subject of international attention, a backlash to this critical historical assessment led to an upsurge in antisemitic rhetoric and what a study indicated was a substantial reduction in inhibitions against racist expressions toward Jews. More recent public opinion polls suggest the Swiss are among Europe’s most antisemitic populations.

An old and unresolved sticking point for Swiss Jews has been the banning of kosher slaughter, which was outlawed in 1874 and remains prohibited to this day. Since 2002, the Swiss government has allowed the importation of kosher meat, but ritual slaughter remains illegal.

For all its significance in Zionist history, Basel appears to have no commemorative plaque or similar tribute marking either its centrality in the birth of the modern Zionist movement or of Herzl’s association with it, although the museum celebrates the connection.

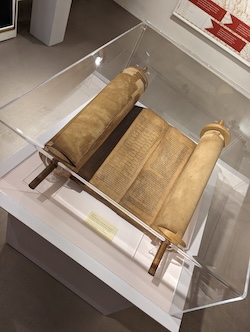

The Jewish Museum of Switzerland is located in a nondescript side street about a 20-minute walk from the Basel train station. It is open Monday to Thursday, 1-4 p.m., and Sundays, 11 a.m.-5 p.m. The permanent exhibition explores Jewish culture, religion and history through an impressive assemblage of ritual objects, documents, household items and testimonies. The current exhibition, Literally Jewish, which runs into next year, explores how Jews have been perceived depending on the time, language and attitude, including, as the introductory material says, “from derogatory to valourizing, ideological to idealizing.” Adult admission is 10 Swiss francs – about $15.50 Canadian – making it one of the more affordable attractions in a country where everything is gobsmackingly expensive.