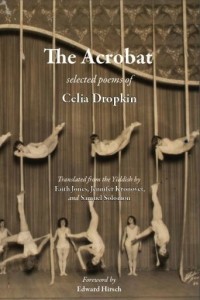

From the moment I read Pat Johnson’s interview with Faith Jones prior to last year’s Limmud, I knew I wanted to read The Acrobat: Selected Poems of Celia Dropkin (Tebot Bach, 2014).

The title of the collection wasn’t mentioned but the topic was: “erotic Yiddish poetry.” Jones, who translated Dropkin’s work into English with Jennifer Kronovet and Samuel Solomon, gave an overview of the poet’s background, which is explained in more detail in The Acrobat. That Dropkin writes with and about such passion is notable given her life’s circumstances. Born in Belarus in 1887, she and her family had to rely on the charity of relatives after her father died. While difficult, it meant that she could receive an education, and she became a writer. In 1909, she married Shmaye Dropkin, a Bund activist whose political activities forced him to flee czarist Russia, and, in 1912, Dropkin (and their son) joined him in New York.

The title of the collection wasn’t mentioned but the topic was: “erotic Yiddish poetry.” Jones, who translated Dropkin’s work into English with Jennifer Kronovet and Samuel Solomon, gave an overview of the poet’s background, which is explained in more detail in The Acrobat. That Dropkin writes with and about such passion is notable given her life’s circumstances. Born in Belarus in 1887, she and her family had to rely on the charity of relatives after her father died. While difficult, it meant that she could receive an education, and she became a writer. In 1909, she married Shmaye Dropkin, a Bund activist whose political activities forced him to flee czarist Russia, and, in 1912, Dropkin (and their son) joined him in New York.

“There,” reads the Translators’ Note, “inspired by the foment of Yiddish culture she found, Dropkin shifted from writing in Russian to writing in Yiddish…. She became a part of the thriving Yiddish literary scene, publishing widely in Yiddish newspapers and literary journals. Yet, she was publicly criticized by her male contemporaries for the perceived extremity of her work. All this time, Dropkin raised five children; a sixth died in infancy. She occasionally wrote stories and novellas in serialization for money, especially during the Depression when her family needed the income. Although the bulk of her oeuvre dates from the 1920s and ’30s, Dropkin never stopped writing poems. She wrote almost until her death in 1956.”

The Acrobat is not a comprehensive collection, but rather, as Jones explained in an interview with Leah Falk at yivo.org, the translators “chose the ones that we thought we could make into good poems in English…. The poems, even some of her quite important poems, that we did not think we knew how to work with, or that lost something in the translation that we didn’t think would be regained, we didn’t keep…. We weren’t able to capture them in the way that we felt really did them justice.”

A page-facing translation – i.e. the Yiddish poem is on the page facing the English version – those who understand Yiddish can not only engage in discussions about a poem’s meanings, but its translation. For example, the title poem, which is generally translated as “The Circus Lady,” gives an idea of the complexity of language, and the different images that are conjured by words that basically mean the same thing.

Dropkin’s poems more than withstand the test of time. Eighty-plus years later, they retain their immediacy. As Edward Hirsch writes in the foreword, Dropkin’s “lyrics come fully loaded. They are erotically frank and emotionally unabashed, deeply engendered, relentlessly truthful. They are terse and musical, like songs, and carefully constructed to explode with maximum impact.”

More than a decade in the making, The Acrobat is, remarkably, the first collection of Dropkin’s work in English, and she could not have gotten a better group of translators. Their love of the poetry comes through, as does their skill. One could almost be forgiven for thinking that Dropkin wrote in English. The Acrobat is truly an inspiring – and sometimes challenging – read. But it is more than that.

In speaking to Johnson, Jones admitted another objective. “I would like people to think about re-envisioning our forbearers as people who were more like us,” she said. “We need to really explore the people in our past and, as a historian, this is what I hope for most: that people will explore the past, understanding that these people were not like us, but in other ways were very much like us.”

In this, she and her colleagues also succeed. This is your bubbe’s poetry, as much as it is yours. And, while thought may be a little unsettling, given some of the subject matter, it is also very cool.

***

He and She

by Celia Dropkin (from The Acrobat)

He is a branch;

she – the green leaves on the branch.

From him to her flows

dark power, thick fertile sap.

She shudders with each touch of wind,

whispers and laughs,

turns the silver

of delighted eyes.

He is simple, mute.

Autumn dyes her deep

colors. The cold wind cruelly

exiles her from the branch,

while he remains the same, simple,

robust, mute.