Noa Baum, one of the presenters at this year’s Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival, is a professional storyteller who, in recent years, has dedicated herself to promoting peace between Israelis and Palestinians. She has taken a long road to get to where she is today.

Baum was born in the late 1950s in Israel and grew up in the “golden age” of Zionism, where, despite the many challenges and flaws of the young state, the shadow of controversial wars and of the occupation had not yet darkened the Israeli self-image.

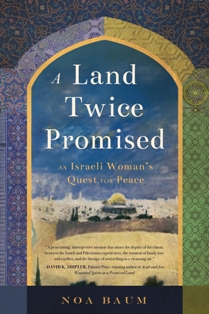

As recounted in her 2016 debut work A Land Twice Promised: An Israeli Woman’s Quest for Peace, Baum grew up with both a deep love of Israel and a keen sense of Jewish vulnerability and the wounds of the Holocaust. The narrative she grew up with about Israel centred on the heroism of its citizen army (“our boys,” she repeatedly calls them) standing up to the bewildering, relentless hatred of the Arab countries. She was deeply shaped by the experience of living through the 1967 Six Day War and the 1973 Yom Kippur War as a child.

As recounted in her 2016 debut work A Land Twice Promised: An Israeli Woman’s Quest for Peace, Baum grew up with both a deep love of Israel and a keen sense of Jewish vulnerability and the wounds of the Holocaust. The narrative she grew up with about Israel centred on the heroism of its citizen army (“our boys,” she repeatedly calls them) standing up to the bewildering, relentless hatred of the Arab countries. She was deeply shaped by the experience of living through the 1967 Six Day War and the 1973 Yom Kippur War as a child.

Over the years, she developed a more nuanced view. She came to face the existence of a hateful, right-wing extreme in Israel and was bitterly disappointed by the actions of the Israeli government in the 1982 Lebanon War, particularly Israeli complicity in the Sabra and Shatila massacre. Her brother, himself named after an uncle who died defending Israel, also suffered post-traumatic stress syndrome from the Lebanon War, leading to a lifelong struggle with mental illness.

When Baum left Israel to move with her husband to the United States to support his career, she left with her simplistic narratives shattered, but an enduring deep love of Israel and the Jewish people.

In her youth, Baum had passionately loved acting and storytelling and, in the United States, she became a professional storyteller. As a tale-spinner, she played it safe, however, presenting upbeat material and folktales and not touching on the conflicts and contradictions of modern Israel. All of that began to change when she nurtured a relationship with another mother, a Palestinian she calls “Jamuna” in the book. As a result of their friendship and the advice of storytelling mentors that she needed to stop shying away from difficult material, Baum began listening to Jamuna’s heart-wrenching stories of growing up Palestinian in the land of Baum’s dreams, with an eye to telling Jamuna’s stories.

“Hearing how the soldiers of the IDF, ‘our boys,’ were to a young Jamuna the source of terror and hatred, was heartwrenching,” Baum told the Independent.

Baum began touring with a one-woman play called A Land Twice Promised, wherein she delivered monologues from the perspectives of herself, her mother, Jamuna and Jamuna’s mother. The show aimed to bring healing and be a contribution toward peace. As one would expect, it was received in many different ways. Baum was called a “traitor” and told she “should be ashamed” of herself; others said she had described their own Israeli or Palestinian experience perfectly. Both Israelis and Palestinians said the show was not balanced enough. One woman from Nigeria said the show made her realize Jews were human beings; others said they’d never felt compassion for Israelis before seeing the show. Some said it was the first time they empathized with Palestinians.

“In the beginning, it was terrifying,” said Baum. “Audience reactions would throw me into bouts of anxiety.”

Gradually, she developed the ability to process the diverse reactions and became confident in what she was doing, and she continued to actively evolve the show based on audience feedback that she solicited.

In 2015, after doing the show for 14 years, Baum was approached by someone interested in making it into a book. It was an offer she couldn’t refuse, though she had never written before. “I’m not really a writer,” she said. “I come from the world of performance, I’m a speaking artist.”

Despite Baum’s lack of writing experience, A Land Twice Promised is a moving, lucid memoir that powerfully evokes the Israeli experience in the last decades, and Baum’s personal and familial struggles to come to terms with it.

The book provokes empathy and insight, and will lead most readers to embrace a view of Israel and the Palestinian conflict that is both complex and compassionate. The book has received favorable reviews and even won many commendations, including one from Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Shipler, writer of Arab and Jew: Wounded Spirits in the Promised Land.

Baum will speak at the book festival on Nov 29 at 6:30 p.m. For tickets and the full festival schedule, visit jccgv.com/content/jewish-book-fest.

Matthew Gindin is a freelance journalist, writer and lecturer. He writes regularly for the Forward and All That Is Interesting, and has been published in Religion Dispatches, Situate Magazine, Tikkun and elsewhere. He can be found on Medium and Twitter.