Martha and Waitstill Sharp at home in Wellesley, Mass., in 1938. (photo from Sharp Family Archives via pbs.org)

At a time when many Americans embraced isolationism, the leaders of the American Unitarian Association were focused on the refugees clamoring to get out of Czechoslovakia. The AUA impelled Unitarian minister Waitstill Sharp to go with his wife Martha to Europe in 1938, leaving their young children in the care of others, and get as many people out as possible with documents and cunning.

Yad Vashem posthumously acknowledged the Sharps as Righteous Among the Nations in 2006. The couple’s saga, and that of several of the Jews they rescued, is recounted in Artemis Joukowsky and Ken Burns’ feature-length documentary Defying the Nazis: The Sharps’ War, which aired earlier this month on PBS.

For those who have seen a film or three about the various efforts to extricate Jews from the deathtrap of Nazi-occupied Europe, Defying the Nazis breaks no new ground. But there are always new generations who aren’t familiar with the Holocaust or cognizant of the courage of ordinary people who saved friends and neighbors or, in the case of the Sharps, complete strangers.

Joukowsky is the Sharps’ grandson, and the curator and guardian of their legacy. Burns, of course, brings household-name recognition and brand-name confidence to a PBS audience, as well as a uniformly high standard of craft and polish. If his name attracts viewers who otherwise wouldn’t tune in, it’s all for the good.

Defying the Nazis arrives at an especially ugly time when refugees and immigrants are being demonized and conflated with terrorists. Not that xenophobia is a new phenomenon, as Jewish readers are especially aware. But I find the film more valuable and inspiring as a reminder that there are highly moral individuals who will put themselves in mortal danger to do the right thing – even if they have no personal stake or connection to the beneficiaries.

Waitstill Sharp was a trained lawyer while Martha had the self-confidence and determination to attend college in a day and age when some families – including hers – disavowed their daughters for not getting a job to augment the household income. That is to say, the Sharps were adept at thinking on their feet, delivering persuasive and succinct arguments and hiding their emotions. Whether counseling desperate applicants in Prague, raising money in London or Paris (like Waitstill did) or accompanying refugees by train across Germany to a safe border (like Martha and Waitstill did, separately), these were essential skills.

The couple was based in the Czech capital for six treacherous months beginning just before the Nazi invasion in March 1939. They were dispatched again the following summer, this time to Lisbon.

As compelling as the Sharps’ activities were, they were relatively brief in duration. There’s only so much to tell, so the filmmakers augment the rescuers’ point of view with context from Holocaust historian Debórah Dwork and the firsthand recollections of several survivors whom the Sharps aided.

Viewers who are fascinated by the ways in which parental choices affect children will enjoy watching and interpreting the passages with the Sharps’ daughter. Martha Jr. admits to being (understandably) upset when her parents took off for Europe, not once but twice, but she touts the remarkable results they achieved rather than channeling a petulant child.

The Sharps may have alienated their daughter, at least for brief periods of her adolescence. They definitely paid a price in their marriage, which didn’t last a decade after the war.

Defying the Nazis doesn’t address it, but I highly doubt the couple had any regrets about embarking on their life-saving refugee work. Consider Waitstill’s succinct reply when the German-Jewish author Lion Feuchtwanger asked why he was taking such an immense risk to help him: “I don’t like to see guys get pushed around,” Sharp said.

Defying the Nazis: The Sharps’ War is available for viewing (at no charge) at pbs.org/kenburns/defying-the-nazis-the-sharps-war/home until Oct. 6.

Michael Fox is a writer and film critic living in San Francisco.

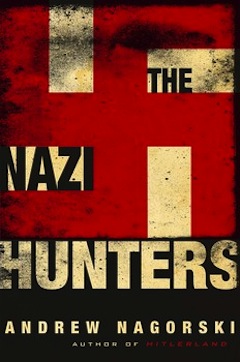

The story of Eichmann’s capture, extra-judicial extradition to Israel, trial and execution is retold in The Nazi Hunters, a book by author and former Newsweek journalist Andrew Nagroski, who will be in Vancouver this fall as part of the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival.

The story of Eichmann’s capture, extra-judicial extradition to Israel, trial and execution is retold in The Nazi Hunters, a book by author and former Newsweek journalist Andrew Nagroski, who will be in Vancouver this fall as part of the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival.