It may not be a total coincidence that one of the most recent conflicts over book banning is taking place in McMinn County, Tenn., less than an hour from the town of Dayton, in the same state, which was the site of the renowned Scopes “Monkey” Trial, 97 years ago.

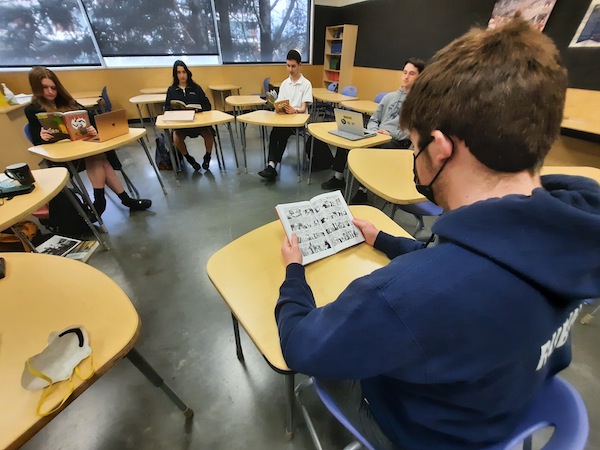

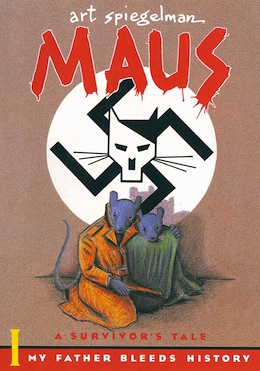

The fight over whether Art Spiegelman’s graphic memoir about the Holocaust, Maus, is suitable reading for high schoolers echoes the earlier debate over whether teaching the theory of evolution was appropriate fare for students in a place and time where the biblical creation story was the only accepted narrative.

The debate over the banning of books and ideas is a hot topic these days, though hardly a new one.

Fortunately, we live in an age when banning ideas is nearly impossible in a free, or even partly free, society. Only in totalitarian and authoritarian regimes are governments able to block information. Around the world, in many countries, gaining access to forbidden ideas is relatively easy. In North America, the New York Public Library, among others, has made it easier for people anywhere to access specifically banned or challenged materials. People who want to seek out publications that authority figures try to limit are generally able to do so.

A phenomenon less easily addressed is the proliferation of misinformation and disinformation. This proliferation is the flip side of the ability to access banned ideas. In a world where anyone with a computer can access information, anyone with a computer can just as easily invent information and then circulate it widely.

Misinformation and disinformation have always existed. But almost certainly never have they so dramatically defined civil discourse. The difference between these two terms is important. One source calls misinformation “false information that is spread, regardless of intent to mislead.” Disinformation, from the same source, is deemed “deliberately misleading or biased information; manipulated narrative or facts; propaganda.” Both are problematic, but intent matters. Misinformation can sometimes be righted through correctives. Disinformation is often formulated in ways that actively deter correction.

For example, the greatest threat to American democracy right now is a narrative that has been formulated in such a perverse, Orwellian manner that the perpetrators of the lie that the 2020 U.S. presidential election was illegitimately “stolen” are the very people who are trying to steal a legitimate election. Those who perpetuate a lie accuse opponents of lying.

The first issue of The Atlantic magazine this year was almost entirely devoted to this subject and the thesis, if we may summarize crudely, is that, unless some dramatic corrective is applied, American democracy has less than two years to survive.

The internet, which is the keystone of our 21st-century ability to read and write virtually anything, has also emerged at a time of massive diffusion of so-called “mainstream media.” The grandchildren of those who grew up with three TV channels can now access thousands. We self-select our information and entertainment, with the impact that we have more, but smaller, frames of reference. One of the results of this is that we have largely been able to choose our own “truths.”

There are no simple solutions to these problems. But, if there is an antidote to ignorance, misinformation and disinformation, it is a recommitment to liberal values of free expression and unbridled academic inquiry. Applied to younger generations, this means inculcating in them an ability to assess and analyze context, information and sources. This sounds like a simple remedy but, of course, learning to think critically is a lifelong pursuit and cannot be taught in a single semester.

Yet, this is the primary way forward. As a society, we need to acknowledge that critical thinking is the foundation upon which democracy and civil society rests. We have abandoned balanced discussion and nuanced consideration of topics in favour of memes and slogans that suit our purposes.

We face a tough crawl out of the hole we find ourselves in – that is, assuming we have stopped digging – but confronting and contending with challenging ideas is the ideal we must strive for. Every banned book is another shovelful of dirt in our democracy’s race to the bottom.