Mordechai Edel beside the personalized ketubah he created for A.J. and Olena Steigman; A.J. is a chess champion and Olena is a classical pianist. (photo from Mordechai Edel)

Vancouver artist Mordechai Edel is one of a handful of people in Canada who make ketubot (singular: ketubah), the standard contract for traditional Jewish marriages, which have been used for millennia.

“I was trained as an impressionist artist, from which I developed the philosophic concept of ‘impression-mystic’ art,” Edel told the Independent. “Hopefully, this contributes in a small way to ‘marrying’ wedding contracts with art and harmonizing the opposites of heaven and earth, chiaroscuro [the use of strong contrasts of dark and light], fire and water.”

While the central theme of a ketubah is constant – an obligation on the part of the groom to provide for his bride – their designs can vary immensely, and each one designed by Edel tells, in its way, a separate story. He has been creating ketubot for 40 years.

“I often incorporate a stylized menorah symbol, which reflects the potential marriage of all humanity uniting together under G-d’s joyous chuppah canopy of shalom [peace and wholeness],” he said.

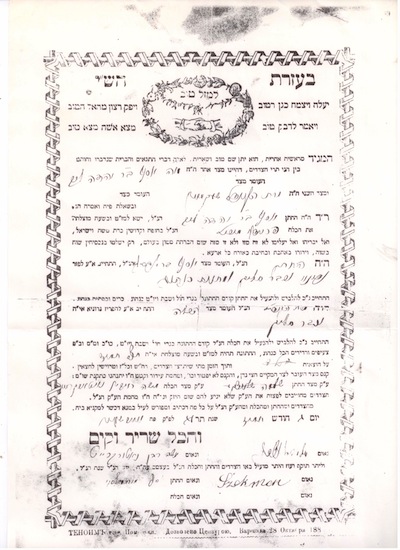

A kosher ketubah requires precision and documentation, especially regarding Hebrew names, marriage location and dates. Ketubot are usually written in Aramaic, in calligraphic style, and halachic (Jewish legal) requirements allow little room for embellishment.

“Not much fun there,” said Edel of the creative possibilities. “However, ‘the fun’ may begin with the surrounding artwork. That’s when personal requests start to kick in. I am often requested to incorporate ‘painted stories,’ illustrating romantic memories of how a couple first met.”

In the past several years, Edel has received numerous ketubah requests from local rabbis, including a “standard house model” developed with Rabbi Andrew Rosenblatt of Congregation Schara Tzedeck.

“Occasionally, some people do still enjoy elaborate weddings, which tend to generate requests for more personalized, sometimes eccentric artwork,” said Edel.

Depending on the couple’s budget, the creative detail of a personalized ketubah can vary substantially, from minimal artwork to the most elaborate designs, he said.

Edel can take several weeks to paint a personalized ketubah, although sometimes it can “just click” and he can finish one in two to three weeks. Ideally, couples planning on getting married would contact him as soon as possible, to give him as much time as possible.

Often, he said, the biggest challenge is to receive accurate place, name, date and time information. Sephardi ketubot do not permit any erasures, whereas Ashkenazi halachah (Jewish law) allows changes before the contract is signed and validated by two kosher witnesses, he explained.

Edel shared an experience that happened during a Sephardi wedding in the mid-2000s. He had painted a calla lily ketubah for a couple that had met in Acapulco, replete with a romantic sunset and a ship setting sail for Jerusalem in the background.

“Guess what? The night before the marriage, the rabbi checked the ketubah and there was one letter, ‘vov,’ missing in the Hebrew spelling of Vancouver. I was told it was invalid, it could not be rectified and was void,” Edel recalled.

The solution, Edel found, was to physically cut out the contract part, leaving the surrounding artwork, forming a window. He then spent the entire night rewriting the document, which he then inserted, forming a two-part ketubah.

“This negative-into-positive transformation has become a trademark blessing that I now incorporate into all commissioned ketubot,” said Edel. “And, in case of a last-minute error or wine spill, all ketubot come with a duplicate backup document.”

Along the way, Edel has received some unique ketubah requests. One couple, who had encountered a skunk on their first date in Stanley Park, asked that the scene be recreated in the marriage contract.

“I had difficulty finding a stinky model who would sit still,” Edel recalled. “That turned out to be a most scentimental ketubah.”

Another couple commissioned a grandiose, oil-on-canvas ketubah to fit over their fireplace. At the wedding ceremony, the three-foot-by-five-foot ketubah was carried into the sanctuary. The audience stood up and, according to Edel, let out an enormous communal “wow!”

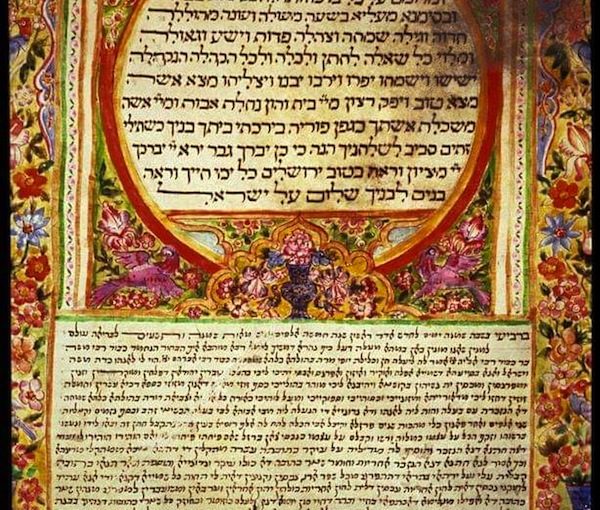

Some of the more exceptional commissions Edel has seen have come from far afield. He recently completed a request that arrived “out of nowhere” from American businessman and professional chess player A.J. Steigman and his bride Olena, a classical pianist. They got married at the Western Wall (Kotel) in Israel and the ketubah features the groom (chatan) playing chess on a Vermeer-style chessboard with the bride (kalla) playing a Shostakovich concerto, all in the foreground of the Kotel.

Edel has also refurbished ketubot. In one instance, he was commissioned by the son-in-law of longstanding Schara Tzedeck members to “enhance” their original 1948 marriage certificate for their 50th anniversary. He created a ketubah “with memories of leaving the shtetl in sepia tones, transported into modern times via heaven’s kohanic [priestly] blessings, and embellished with a gorgeous bouquet of their favourite, fragrant rose flowers.”

One of Edel’s ketubot, “Le Picnique,” began as a painting commissioned by the late Joe and Rosalie Segal to be viewed by residents and staff at the Louis Brier Home and Hospital. “It later developed into a ketubah as a joyous tribute to this wonderful, caring couple,” said Edel.

Edel is grateful for the many blessings he has received in life, and gives special thanks to his wife, Annie, who helps design the ketubot.

“It is humbly interesting to note that the surname Edel means fine and noble, whereas a play on words of Mordechai suggests the French amour de chai or love of life,” Edel said. “It is this joyous love of life partnership that characterizes our ketubot and relationship between G-d, bride and groom and artist.”

For more information about Edel’s art and his ketubot, visit edelartworks.com.

Sam Margolis has written for the Globe and Mail, the National Post, UPI and MSNBC.