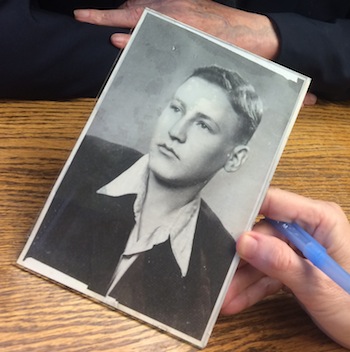

Chaim Kornfeld (photo by Shula Klinger)

In February, the Louis Brier Jewish Aged Foundation and Louis Brier Home and Hospital honoured Chaim Kornfeld. And they did so in the place he has especially dedicated his time over the last four decades: the Louis Brier synagogue.

Chaim was born in Hungary in 1926. His upbringing and education were Orthodox and, for the first part of the Second World War, his family were untouched. From the start of his education at Yiddish cheder, at age 3, he was a good student. Community life continued much as it had for centuries.

Outside the home, Chaim’s memories describe a tense separation between Jew and non-Jew. “My father always used to say, ‘When you see a Shaygetz, cross the street. Go on the other side.’”

Needless to say, young Chaim did not always do as he was told. “I took the beating instead – but I fought back, too.” He adds, “Especially at Easter time, they’d call you dirty Jew.”

It’s not hard to imagine a young Chaim’s spirited response. Even at 90, he is energetic and expressive in conversation. “I was a tough kid,” he says. His daughter Tova adds with pride, “He gave as good as he got!”

In 1944, Chaim was preparing to go to Franz Josef National Rabbinical Seminary of Hungary in Budapest. Then, not long before his 17th birthday, his family was moved to a ghetto with the other Jews of their town. Then came the trains.

Chaim, his parents and one of his sisters were sent to Auschwitz. On the journey, Chaim was permitted to fill a bucket of water for the passengers to have occasional drinks. He also took the dead out of the car.

On arriving at the concentration camp, Chaim jumped out. Greeted with ordinary scenes – “children playing, laundry drying” – Chaim’s mother figured she could work in the camp laundry.

Chaim relates how “an old man came up and asked, ‘Do you speak Yiddish?’ I said, ‘Yes, of course.’” The man pointed to a German official. “He’s going to ask you two questions. When he asks how old you are, you say you’re 18. When he asks you what you do, say you’re a farmer.”

Young Chaim approached the man with his usual confidence. Josef Mengele asked him his age and profession. Chaim answered as he’d been told. Mengele told him to go to the right. His parents were sent to the left. Before they were separated, Chaim’s father made a final request: “Bleib a Yid.” (“Remain a Jew.”) Afterwards, Chaim heard others say, “You see that smoke? That’s your parents.”

At Auschwitz, the Nazis stripped the prisoners of their belongings and identity, shaving off Chaim’s hair. He smiles ruefully. “I had lovely peyis, nice and curly.” Having only spent two weeks in Auschwitz before being transferred to Mauthausen in Austria, Chaim wasn’t at the camp long enough to get a number tattooed on his arm. He has not forgotten his number, though, and barks out “67655!” at an impressive volume, but not in English, or even Yiddish. It’s in Polish, as he heard it at Auschwitz.

Asked how he managed to maintain his sanity while facing death every day, he quotes Robert Frost: “I had promises to keep and many miles to go before I sleep.” But there’s more to it. Chaim describes how he kept his promise to his father, in spite of malnutrition and brutal treatment. “I always said, I’ll get out of here.”

He speaks with gritted teeth. “I never gave up. Even when I worked in a tunnel underground, I was mumbling a prayer. I prayed all the time to make time go faster. I knew the prayers by heart from a very young age. All kinds.”

Chaim describes a life of hard labour, misery and oppression. There were about 600 steps up the quarry. We “carried rocks on our shoulders, every day. There were dogs barking, soldiers pointing guns at us.” There was a pond at the bottom. If a prisoner fell down, he says, they would be pushed in.

Chaim found that he was the only one who remembered long tracts of the Torah. He led Kol Nidre in the camp, “all the others stood around me. I knew it by heart. I got a good education.” To lead a service in such appalling circumstances takes more than just education, however. It speaks to a capacity for leadership and clarity in a situation that is baffling in its cruelty.

When the prisoners were forced on a death march, Chaim was recuperating from an abscessed ankle. Although barely able to stand, he followed the advice of a fellow prisoner, who told him that if he didn’t leave the camp upright, he’d never leave at all. Limping in extreme pain, Chaim made it out but collapsed afterwards. When an SS officer raised his gun to shoot him, Chaim spoke up with his characteristic blend of optimism and boldness. Having been reminded of what a good worker this young Jew was, the officer permitted Chaim to hitch a ride on a passing wagon.

Until this year, Chaim was active in Holocaust education. In spite of the many letters from kids, thanking him for his work, these letters can be “painful,” he says. “The reminder is not always pleasant.” One might think that even a “tough kid” could tire of telling this harrowing story again and again, but Chaim isn’t flagging. “As long as there’s someone to listen, I’ll tell.”

After liberation, Chaim lived at the “internat” (boarding school) maintained by the rabbinical college in Budapest. Completing two years of high school in one under the instruction of one Dr. Kolben, Chaim still speaks admiringly of his teacher. “She was quite a lady. Very smart,” he says.

Kolben also taught them about the culture of Budapest. It gave the boys a chance to revive their appreciation of the arts, to leave them with images of beauty, after the horrors of the war. These included trips to the theatre in Budapest, to see Shakespeare’s plays. Their influence lives on today in Chaim’s memory. “To be or not to be, that is the question, whether it is nobler.…” He pauses to let me finish the quote. After staring, dazed, for an instant, I am relieved to find “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” bubble up in my mind.

Chaim ended up in a displaced persons camp, in Bari, Italy. The hungry residents were frustrated to find that the food stores were locked away. “He led an uprising and they opened the locker,” Tova says. “He gave an impassioned speech.”

After the DP camp came aliyah. “Someone came from the JDC [Joint Distribution Committee] to take people to Palestine.” Chaim arrived in 1949, right after independence, and joined the air force immediately. “I was in charge of a platoon of women. That was fun,” he laughs. “I told them, during the day, I am in charge. In the evening, you are in charge!”

Asked about his career, he describes being “a lawyer for 55 years; prosecuting, judging, the lot!” Indeed, Chaim was appointed to the bench. Having developed a habit of quoting the Talmud in his judgments, he earned the nickname “The Bible Judge.” He would make “off the bench decisions,” which were popular with the courts, Tova recalls.

Chaim had originally planned to go to engineering school but his English was not fluent enough. “It was so hard, so technical,” he says. At the end of his first year, his essay about George Bernard Shaw’s Candida got him a C-. “People who were born and raised in Canada failed that exam!” he says proudly of his grade.

His optimistic attitude was evident in his approach to work as well. As a lawyer, he was known for handing out treats at the courthouse. Known as “Candy Man,” he would move up lines of people waiting for their paperwork, greeted by out-stretched hands.

At the Feb. 25 Louis Brier tribute, Chaim was honoured with a special Shabbat service in his name. With more than 150 people in attendance, Chaim read Haftorah. As Tova, says, “like a bar mitzvah boy, beautiful.” Thanked by many for his work, he was given a Torah cover for one of Louis Brier’s volumes. Says Tova, “It was really lovely.”

Reflecting back on his survival, Chaim credits his Judaism for keeping him afloat. This is living proof of Viktor Frankl’s assertion that, to survive, one needed to seek a meaning to one’s existence, even in the camps. “I didn’t feel that G-d abandoned me,” says Chaim. “I never lost my faith.”

Indeed, he has kept a kosher home for all of his adult life. But survival takes resilience and a good deal of ingenuity, as well as faith. “We took empty burlap bags and stuffed them into our pyjamas, to stay warm,” he says. When he was starving, he ate coal. “I was my own doctor,” he says.

One might think these experiences would define him, but, when presented with the term “survivor,” he shrugs and grimaces. “Rachmanut saneiti,” he adds. “I hate pity.”

One cannot help but see the sense in Chaim’s attitude. Simply referring to this man as a Holocaust survivor would be reductive. He recently celebrated six decades of marriage to his wife, Aliza, and their four adult children all have successful careers. Still active at 90, he has built a reputation as a mensch: generous, respectful, with a buoyant spirit and a talent for relationship-building. And, even now, one sees the tough kid – the keeper of promises, the kid who took a beating rather than tolerate bigotry. And, the same kid who jumped off the train in 1944, ready to meet the eye of the man who held – and toyed with, tortured and destroyed – the lives of his contemporaries.

Chaim has only just retired. He still reads the Tanach in his office and attends shul on Saturdays and Sundays. He talks of keeping up with his hobbies: “Swimming at the JCC every day. Making my wife happy.”

Shula Klinger is an author, illustrator and journalist living in North Vancouver. Find out more at niftyscissors.com.