For many of us, it is hard to get excited about a subject until we can experience it, or meet someone who has. Historical fiction can bridge the gap between simply memorizing dates and names to empathizing with those affected and taking what we learn into our lives.

Two recent Second Story Press publications do an excellent job of teaching and engaging younger readers. They also provide a starting point for these readers and their parents, family, friends and educators to discuss difficult and sensitive topics that not only relate to the past, but to current situations, as well.

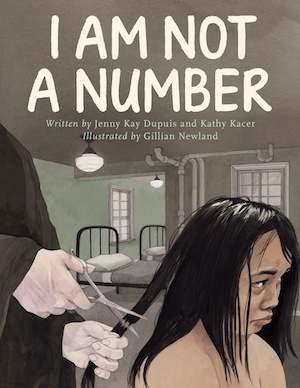

The Ship to Nowhere: On Board the Exodus by Rona Arato (for ages 9 to 13) tells the story of the ship Exodus 1947 through the eyes of 11-year-old Rachel Landesman. I Am Not a Number by Jenny Kay Dupuis and Kathy Kacer and illustrated by Gillian Newland (for ages 7 to 11) tells the story of 8-year-old Irene Couchie, who is forcibly taken from her First Nations family and home to live in a residential school in 1928. Both Rachel and Irene are real people.

Sadly, their stories are representative of what also happened to countless others. And, even more sadly, what continues to happen. The Ship to Nowhere could lead to a conversation about the Syrian refugee crisis and antisemitism in Canada and elsewhere. I Am Not a Number brings to mind some parallels between the Holocaust and the attempted genocide of Canada’s First Nations, as well as the inequalities that still exist in Canada, the treaties that have not been ratified, the reconciliation over the residential schools that is long overdue and has barely begun.

Given the ages of their intended readers, both of these books tread lightly – that said, they deliver powerful messages and succeed in their missions to educate.

The illustrations in I Am Not a Number, a hardcover picture book, are as revealing as the text. Irene and her siblings, as they huddle behind their father when the government agent comes to take her and two of her brothers away; the sadness on Irene’s face as a nun cuts her hair, the anger as she sits in church; and the unbridled joy when she and her brothers are back at home after a tortuous year – these are just some of the emotions Newland movingly captures.

The illustrations in I Am Not a Number, a hardcover picture book, are as revealing as the text. Irene and her siblings, as they huddle behind their father when the government agent comes to take her and two of her brothers away; the sadness on Irene’s face as a nun cuts her hair, the anger as she sits in church; and the unbridled joy when she and her brothers are back at home after a tortuous year – these are just some of the emotions Newland movingly captures.

And Kay Dupuis tells her grandmother’s story with such love. This was a family that was strong and, in the end, luckier than many, in that Irene and her brothers didn’t return to the residential school – when they came home for the summer, their family kept them hidden from the government agent.

I Am Not a Number includes a brief overview of the residential school system, and mention of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Kay Dupuis also tells readers a bit more about her grandmother in an afterword, where there are a few photos of the Couchie family.

The Ship to Nowhere has photos throughout, and Arato uses the author’s note at the end to let readers briefly know what happened to Rachel, Rachel’s mom and sisters (her dad was killed in the Holocaust), the ship’s captain, Yitzhak Aronowicz (known as Captain Ike) and one of the journalists who doggedly reported to the world the Exodus’s journey, Ruth Gruber.

Since it is for older young readers, there are parts of The Ship to Nowhere that are quite graphic – the incredible brutality of the British is well-depicted, as are Britain’s efforts to prevent the ship’s 4,500-plus Holocaust survivors from knowing what the media were reporting on their treatment. Even with the passage of time, the anger boils in reading about how these survivors were tear-gassed and beaten (in some cases to death) on the Exodus, forced to live as captives on three other ships after they were turned out of Palestine, and again beaten and manhandled if they refused to leave their ships in Germany, where the British took them eventually, to live in refugee camps.

There are many touching moments between the crew and their passengers and between fellow refugees. It is important to be reminded that France offered to take in all of the refugees; an offer that was declined. And it would be nice to think that, at the least, the Exodus’s plight positively influenced some United Nations members to vote in favour of the creation of Israel.