A painting from Pompeii showing gladiators fighting. It is housed in the National Archeology Museum in Naples. (photo by Deborah Rubin Fields)

Among the fabulous finds of Pompeii is the helmet of an apparently Jewish gladiator. Who would have thought?

As many readers might know, Pompeii was the unfortunate recipient of Mount Vesuvius’s 79 CE wrath. Many gladiator helmets have been dug up in Pompeii’s excavations. (Unfortunately, this collection is kept in storage at Naples’ National Archeology Museum.)

In the paper “A Jewish Gladiator in Pompeii,” historian Dr. Samuele Rocca notes that one of these stored helmets stands out for its unique decoration. While there are images on other recovered helmets and weapons, they usually come from pagan iconography. On this one helmet’s forehead relief, however, there is a seven-branched palmetto tree with a cluster of dates on each side.

During the time of the gladiators, the palmetto symbol was apparently employed in only one other place – as an engraving on Judaean coins. These coins, Rocca says, were associated with Jews. Indeed, the symbol was jointly chosen by the local Jewish leadership and the Roman procurator. Thus, the palm tree symbolized both the religious and secular ideals of the late Second Temple Jewish leadership.

Moreover, Rocca reports that a small number of other Jews came to Pompeii both before the exile of 70 CE and afterward. In Pompeii, they did not form a Jewish community as such, but apparently Jewish women lived at Pompeii.

Remarkably, archeologists have excavated lists of Pompeian names. Apparently, during this time, Maria was a Jewish name. One Pompeii woman bearing that name worked with textiles.

Another woman with the same name lived in the Casa dei Quattro Stili, although her rank and societal position remain a mystery. It is theorized that the most well-known Maria was a prostitute, who worked in the Thermopolium of Asellina, in Via dell’Abbondanza.

While Prof. Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, in Herculaneum, Past and Present, writes that food could not have stayed hot in the thermopolia’s terracotta containers, others maintain that the thermopolia were the precursors of today’s restaurants. In brief, this explanation makes a case for Maria to have been a barmaid or waitress.

Estimates are that, in 70 CE, Titus took 20,000 Jewish slaves to Rome, so it is not surprising that Jews arrived in Pompeii as slaves. In fact, from the many documents salvaged from Herculaneum – another town severely affected by that same Vesuvius eruption – we know that Roman society was organized along the lines of freeborn, enslaved, freed and those holding a special status. According to Wallace-Hadrill, “It is a society in which your legal status has an overwhelming importance…. But a society characterized by movement between status groups … the third group comprised those who were neither freeborn nor regularly set free … but who had nevertheless … been promoted to full citizenship.” On still-legible marble panels listing residents’ names, he writes, “only a sixth of the Roman male citizens in Herculaneum could name their freeborn fathers … it leaves them massively outnumbered.”

After Mount Vesuvius’s horrific 79 CE eruption, you may well wonder how so much Herculaneum documentation is still available. Wallace-Hadrill explains, “Pompeii was blanketed in ash and pumice pebbles, while Herculaneum was covered in the fine, hot dust of pyroclastic surges and flows, result[ing] in the extensive preservation at Herculaneum of organic material – principally wood, but also foodstuffs, papyrus and cloth.”

As somewhat of an aside, Salvatore Ciro Nappo, in Pompeii, notes that the Pompeians apparently did not consider Mount Vesuvius dangerous. One indication of this is that the House of the Centenary has a lararium (shrine niche for household gods) fresco in the servants’ rooms showing Bacchus, a thyrsus (a type of staff or wand) and a panther in front of the mountain. Vineyards entirely cover the mountain, presumably indicating Vesuvius brought festivity and prosperity.

Today, archeology is, for the most part, an appreciated study, but that was not always the case. According to Wallace-Hadrill, when medieval rulers wanted to tunnel down into the ruins of Pompeii, they ran into opposition from the Inquisition. Sanctioned excavation – haphazard as it first was, with some kings taking “the good stuff” or even going so far as to destroy finds so as not to share the wealth – did not begin until the 1700s.

Archeology has shown that nearby Naples, located 14 miles southeast of Pompeii, had a bona fide Jewish community pre-dating the Jewish arrival in Pompeii. For trade reasons, Jews started settling in this port city in the first century BCE. Life was tolerable for them, even as the Roman Empire started falling apart. When, in the late fifth and sixth centuries CE, Justinian tried to regain the Roman Empire from the Germanic Ostrogoths, the Jews of Naples fought against Justinian.

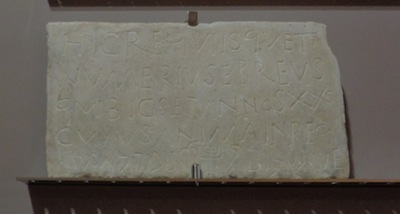

These Jews apparently “blended in” to the extent that they inscribed their tombstones almost entirely in Greek or Latin. Significantly, while the travertine (the land-formed version of limestone) grave markers at Naples’ National Archeology Museum are usually not in chiseled Hebrew, they do contain obvious Jewish symbols such as menorot, lulavim, etrogim and shofarot. On one tombstone, the inscription reads: “Here lies Numerius, a Jew, who lived for 26 years and whose soul is in peace. Shalom, Numeri[u]s, amen.”

The French Angevins oppressed the Jews in the 13th century, but their Aragon successors (in the 1400s) basically left them in peace. Naples thus became a major centre of Jewish book production during the 15th century. Then, as happened in other European countries, the Jews were expelled in 1541, only allowed back in generations later. In the 1800s, the Rothschilds, who were the banking concern in Naples, helped restart the Jewish community. In the 1920s, the community grew to 1,000. While 80% of Italian Jewry survived the Holocaust, Naples’ current Jewish population is about half its former size, with even fewer people belonging to Naples’ synagogue.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.