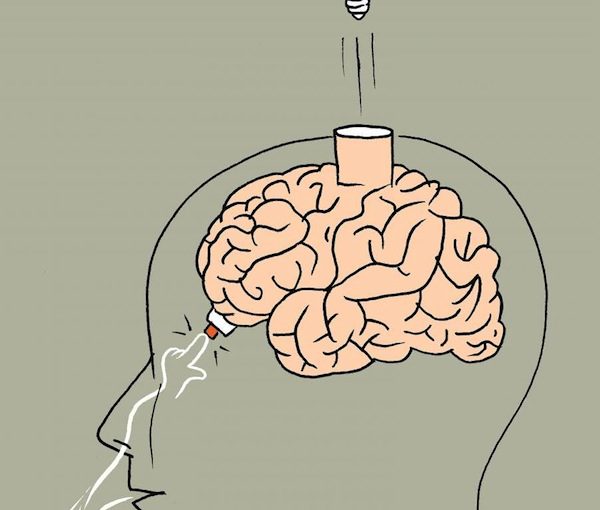

Subjects given problems to solve as they inhaled did better on tests. (image from wis-wander.weizmann.ac.il)

A shot of espresso, a piece of chocolate or a headstand – all of these have been recommended before taking a big test. The best advice, however, could be to take a deep breath. According to research conducted in the lab of Prof. Noam Sobel of the Weizmann Institute of Science’s neurobiology department, people who inhaled when presented with a visuospatial task were better at completing it than those who exhaled in the same situation. The results of the study, which were published in Nature Human Behavior, suggest that the olfactory system may have shaped the evolution of brain function far beyond the basic function of smelling.

Dr. Ofer Perl, who led the research as a graduate student in Sobel’s lab, explained that smell is the most ancient sense. “Even plants and bacteria can ‘smell’ molecules in their environment and react,” said Perl. “But all terrestrial mammals smell by taking air in through their nasal passages and passing signals through nerves into the brain.”

Some theories suggest that this ancient sense set the pattern for the development of other parts of the brain. That is, each additional sense evolved using the template that had previously been set out by the earlier ones. From there, the idea arose that inhalation, in and of itself, might prepare the brain for taking in new information – in essence, synchronizing the two processes.

Indeed, studies from the 1940s on have found that the areas of the brain that are involved in processing smell – and thus in inhalation – are connected with those that create new memories. But the new study started with the hypothesis that parts of the brain involved in higher cognitive functioning may also have evolved along the same basic template, even if these have no ties whatsoever to the sense of smell.

“In other mammals, the sense of smell, inhalation and information processing go together,” said Sobel. “Our hypothesis stated that it is not just the olfactory system, but the entire brain that gets ready for processing new information upon inhalation. We think of this as the ‘sniffing brain.’”

To test their hypothesis, the researchers designed an experiment in which they could measure the airflow through the nostrils of subjects and, at the same time, present them with test problems to solve. These included math problems, spatial visualization problems (in which they had to decide if a drawing of a three-dimensional figure could exist in reality) and verbal tests (in which they had to decide whether the words presented on the screen were real). The subjects were asked to click on a button twice – once when they had answered a question and once when they were ready for the next question. The researchers noted that, as the subjects went through the problems, they took in air just before pressing the button for the question.

The experiment was designed so the researchers could ensure the subjects were not aware that their inhalations were being monitored, and they ruled out a scenario in which the button pushing itself was reason for inhaling, rather than preparation for the task.

Next, the researchers changed the format around, giving subjects only the spatial problems to solve, but half were presented as the test-takers inhaled, half as they exhaled. Inhalation turned out to be significantly tied to successful completion of the test problems. During the experiment, the researchers measured the subjects’ electric brain activity with EEG and here, too, they found differences between inhaling and exhaling, especially in connectivity between different parts of the brain. This was true during rest periods as well as in problem-solving, with greater connectivity linked to inhaling. Moreover, the larger the gap between the two levels of connectivity, the more inhaling appeared to help the subjects solve problems.

“One might think that the brain associates inhaling with oxygenation and thus prepares itself to better focus on test questions, but the time frame does not fit,” said Sobel. “It happens within 200 milliseconds – long before oxygen gets from the lungs to the brain. Our results show that it is not only the olfactory system that is sensitive to inhalation and exhalation – it is the entire brain. We think that we could generalize, and say that the brain works better with inhalation.”

The findings could help explain, among other things, why the world seems fuzzy when our noses are stuffed. Sobel points out that the very word “inspiration” means both to breathe in and to move the intellect or emotions. And those who practise meditation know that the breath is key to controlling emotions and thoughts. This, though, is important empirical support for these intuitions, and it shows that our sense of smell, in some way, most likely provided the prototype for the evolution of the rest of our brain.

The scientists think their findings may, among other things, lead to research into methods to help children and adults with attention and learning disorders improve their skills through controlled nasal breathing.

Sobel’s research is supported by the Azrieli National Institute for Human Brain Imaging and Research; the Norman and Helen Asher Centre for Human Brain Imaging; the Nadia Jaglom Laboratory for the Research in the Neurobiology of Olfaction; the Fondation Adelis; the Rob and Cheryl McEwen Fund for Brain Research; and the European Research Council. Sobel is the incumbent of the Sara and Michael Sela Professorial Chair of Neurobiology.

For the latest Weizmann Institute news, visit wis-wander.weizmann.ac.il.