During the Goldene Medina exhibit this past summer, the documentary Leah, Teddy and the Mandolin was screened. It will be shown again on Dec. 8 at Congregation Beth Israel. (photo from Steve Rom)

I have a bad case of South African Jewish envy. This condition developed when I moved to Vancouver from the North End of Winnipeg. I can’t remember meeting even one South African Jew while growing up in the Prairies – the majority of Jews in my hometown were from Eastern Europe. However, I met oodles of South African Jews when I moved here in the early 1990s and I was impressed by their knowledge of Judaism and their commitment to Jewish life. There seemed to be something unique about their community and it seemed exotic compared to Winnipeg’s. Many of them became my good friends, perhaps because, as a Litvak (my last name literally means a Jew from Lithuania), I share a common ancestry with my South African co-religionists, who predominately hail from Lithuania.

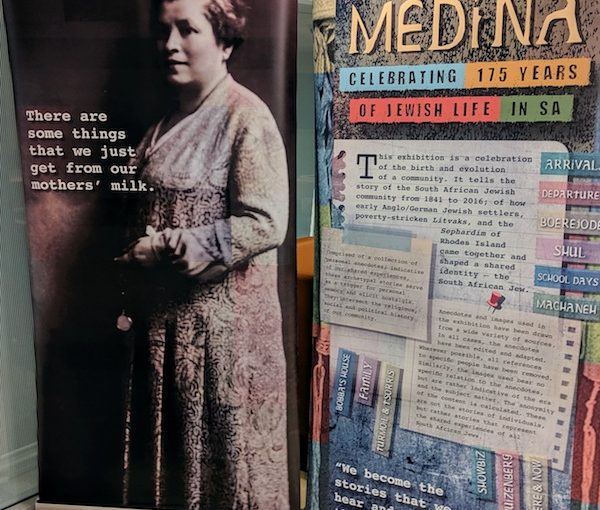

When I first moved here, my South African friend Geoff Sachs, z”l, two Montrealers and I organized Tschayniks, an evening of Jewish performing arts at the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver. It was at the JCC that I met another South African friend, Steve Rom, who was working there at the time, and helped us set up our events. About a month ago, Steve brought a fascinating exhibit to Congregation Beth Israel. Prior to being mounted in Vancouver, the exhibit, Goldene Medina, a celebration of 175 years of Jewish life in South Africa, was displayed in South Africa, Israel and Australia. Thanks to Steve, Jews in Vancouver got a taste of South African Jewish life, as well.

A unique feature of the exhibit was that nobody was named or personally identified on any of the displays. This approach helped tell the story of all South African Jews, and made the exhibit simultaneously particular and universal.

Stories were depicted on a series of panels, and traced the South African Jewish community from its origins in 1841 – when Jews first settled in South Africa – to the present. On one of the panels, I recognized the son and daughter in-law of Cecil Hershler, who has South African roots and is well known in the Vancouver Jewish community as a storyteller. His son married a woman from Zimbabwe and the wedding in Vancouver, which I attended, was a joyous blend of South African and Zimbabwean cultures. Seeing the panel brought back memories of that happy occasion and gave me an unexpected personal connection to the exhibit (other than identifying with my Lithuanian landsmen).

Other panels depicted various aspects of Jewish life in South Africa. While I was fascinated by the differences between the South African Jewish community and my experience growing up in Winnipeg, the exhibit was really a microcosm of Jewish life in the Diaspora. For example, the panel on Muizenberg depicted the resort town located near Cape Town, where throngs of South African Jews flocked to during the summer. The photos of crowded beaches told a thousand stories. However, that panel also reminded me of the stories that my dad, z”l, told me about taking the train to Winnipeg Beach in the summer with other Jews from the city to escape the summer heat. Like at Muizenberg, there was a synagogue at Winnipeg Beach. I am sure that Jews from New York have similar stories of escaping the city heat by going to the Catskills. In addition, the Jews of America, like the Jews of South Africa, referred to their new home as “the Goldene Medina.” Ultimately, all three places – Canada, the United States and South Africa – represented a new start for Jews fleeing persecution in Eastern Europe.

The Goldene Medina exhibit gave me an opportunity to learn about Jews from the land of my ancestors in Lithuania, who were able to reinvent themselves on the African continent and create a thriving Jewish community, which, at one point, reached 120,000. This resiliency is a characteristic of Jews and Jewish communities all over the world. And this resilience was evident in the film Leah, Teddy and the Mandolin: Cape Town Embraces Yiddish Song, which screened at Beth Israel during the exhibit – and will be shown again at the synagogue on Dec. 8.

Using 10 years of archival footage, Leah, Teddy and the Mandolin showcases the Annual Leah Todres Yiddish Song Festival, which was held in Cape Town. The documentary features stirring renditions of classic Yiddish songs like “Romania Romania” and “Mayn Shtetele Belz,” as well as two original songs written for the festival by Hal Shaper, a renowned songwriter, which are sung with passion by talented South African Jews of all ages. The songs featured in the film evoke a yearning for a Jewish world that no longer exists in Lithuania and Eastern Europe and highlight the power of the Yiddish language and music.

While the South African Jewish community has shrunk since its heyday in the 1970s to approximately 50,000, it is still an important Diaspora community. In addition, South African Jews make important contributions to every Jewish community they move to, and bring their unique culture to their new homes.

Seeing the exhibit and the documentary cemented the kinship I feel with my South African brothers and sisters. A few of my South African friends even dubbed me an honourary South African Jew at the exhibit, an honour I gladly accepted. One day, I hope to make a pilgrimage to the land of the Litvaks to experience South African Jewish life firsthand. Until then, I will have to continue to learn about South Africa vicariously.

The Dec. 8 screening of Leah, Teddy and the Mandolin at Beth Israel takes place at 4 p.m. Admission is a suggested donation of $10. For more information, visit leahteddyandthemandolin.com.

David J. Litvak is a prairie refugee from the North End of Winnipeg who is a freelance writer, former Voice of Peace and Co-op Radio broadcaster and an “accidental publicist.” His articles have been published in the Forward, Globe and Mail and Seattle Post-Intelligencer. His website is cascadiapublicity.com.