A supply convoy entering Jerusalem, 1948. (image from Shaar Hagai Heritage Museum)

Having just marked Yom Hazikaron and Israel’s 73rd anniversary, it is an appropriate time to recall a piece of Israel’s foundational history, and a new museum that commemorates it.

Seventy-four years ago, the road to Jerusalem was a site of easy ambush. Probably no part of the road was more treacherous than the area around Shaar Hagai. This spot, called Bab el Wad in Arabic, translates into English as the Gate of the Valley. As far back as 1868, French explorer Victor Guerin recognized and commented on this weak spot: he pointed out that the track was so narrow that “a determined band of men could stop an army in it with little difficulty.”

Admittedly, as you today drive on a smooth, paved, two-way, divided Jerusalem/Tel Aviv highway, it is hard to appreciate this reality. But, on Nov. 29, 1947 – the day after the vote on the United Nations Partition Plan, enabling the establishment of the Jewish state – Arab forces began blocking the route to Jerusalem. Not only were Jewish forces shot at, but, because the road curves, drivers couldn’t see where the road was blocked until they were trapped basically.

In David Dayan’s book Roadblock at Shaar Hagai: Creating a State (title translated from the Hebrew), Amos Kochavi recalled one such incident: “The time was approximately two in the afternoon. The long line entered the narrow and dangerous part. They could be anywhere…. We continued to climb … and there was a mighty explosion. The bomb under the road left a huge hole and the convoy stopped. Immediately, terrible shooting began…. We returned fire, but we couldn’t advance. Some of the drivers went into shock…. One driver with shell shock, screamed, ‘I can’t handle it anymore. I’m leaving.’ We yelled back: ‘Don’t move! You won’t come out alive!’ He didn’t hear, jumped from the car and was instantly killed.

“They tried to come down from the hills to get close to the cars, but our fire stopped them. They fire, we fire and the hours go by. No cars have air left in their tires. The number of injured grew. Shalom volunteered … he lay on the road, rolling – to avoid snipers – for a long hour … directing the drivers, one by one, until he had rescued all the cars…. An Australian captain ordered tanks that escorted us back to Gezer. The time was already two at night – 12 hours from when we entered Shaar Hagai.”

Jerusalem was under siege. Essential supplies could not reach the civilian and military population of the city. Jerusalem was dependent on supplies from the rest of the country, and was threatened with being totally cut off from the rest of the country. The only way to reach Jewish Jerusalem was to travel in convoy. (For more information, visit the National Library of Israel website, nli.org.il/en.)

According to the late Sir Martin Gilbert, by the spring of 1948, “Fewer and fewer Jewish food convoys were able to get through to Jerusalem. Towards the end of March, a food convoy failed, for the first time, to get through at all. One food convoy that did get through in March had taken 10 days to do so. By the end of the first week of April, there was only enough flour in Jewish Jerusalem to last for 30 days. Meat, fish, milk and eggs were unobtainable, except in small quantities, for children. The shortage of vegetables was such that children were sent into the fields to collect a weed … known as halamith, it tasted somewhat like spinach, and could be made into soup.” (See Jerusalem in the 20th Century.)

There was also a severe shortage of water. Three days before the state of Israel officially came into existence, the Palestine Post reported that “Jerusalem was still without water yesterday. The two pipelines from Ras el Ein, which were blown up by Arabs between Latrun and Bal el Wad on Friday, have still to be repaired. Crews are scheduled to leave under army escort this morning to continue repair work and, barring further trouble, repairs may be completed today. Water may be pumped into Jerusalem within a few days, according to one municipal official.” So grim was Jerusalem’s situation that archival photos show residents standing in long lines waiting to get their water ration and others rummaging through garbage, in the hopes of finding scraps of food.

Palmach fighters and, even more remarkable, simple truck drivers decided to do whatever they could to keep Jerusalem from being blocked. One now quite senior man, who drove a truck full of live fish for the Sabbath, was interviewed. He recalled looking out his side mirrors to see water streaming from the sides of the vehicle. The truck had been shot in numerous spots. Somehow, he managed to get to Kiryat Anavim, a kibbutz in the Jerusalem Corridor. There, women plugged up the bullet holes with rags. Probably, many of us would have considered giving up at this point, but this driver continued the slow climb to Jerusalem.

The fighters were mostly young people. A significant number were under the age of 18 (today’s conscription age). They came from all backgrounds, religious and non-religious, and from all parts of the country; some were Holocaust survivors. As a number of the fighters had been assigned the task of digging gravesites at Kiryat Anavim, they probably realized they might not survive on the road to Jerusalem.

It was crucial to find a different route for the convoys. Palmach soldiers discovered a detour that went through a hidden valley south of the heavily fortified fortress at Latrun and joined a path descending from Jerusalem. Using heavy tractors, the Palmach slowly cleared a path for vehicles. A water pipeline was also installed along it. The lifeline to the Jews in Jerusalem was secured, providing vital water and other supplies, in the summer months of 1948.

At the point where the road was most unsafe, there is a 19th-century Turkish-built travelers’ khan or inn. On March 23, 2021, Israel’s last election day, a memorial museum was opened at this historic location. The Shaar Hagai Heritage Museum is dedicated to the men and women who prevented Jerusalem from being disconnected in the days leading up to and even following Israel’s independence.

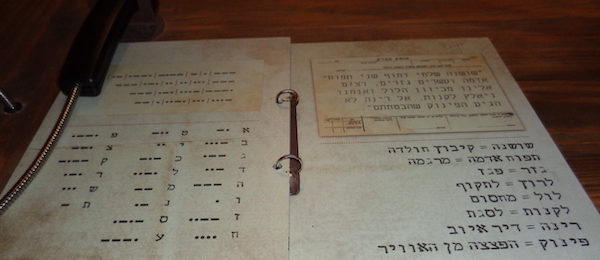

The museum deals less with the chronology of the battles and more with the physical and emotional difficulties convoy members faced, such as confronting dilemmas like whether the trucks should carry guns or food to besieged Jerusalem. There are displays of items used by the convoys, such as codebooks, handguns and rifles. And there are interviews with people who took part in the convoy operations, and part of the exhibit is animated.

Once we are again allowed to travel, the museum is worth a visit on your next trip to Israel. Allow at least an hour-and-a-half for the whole tour, which is recommended for viewers 10 years of age and older. The new museum requires visitors to make advance online reservations, and there are admission fees.

For Hebrew speakers, there’s a preview of the museum at parks.org.il/new/chan.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.