Jacob Dinezon (1856-1919) was a Yiddish novelist and short-story writer, as famous during his lifetime as were his contemporaries, the three pillars of late-19th- and early-20th-century Yiddish literature, Mendele Mocher Sforim, Y.L. Peretz and Sholem Aleichem. All of these masters knew and were impressed with Dinezon’s work.

During his period of literary activity in the latter half of the 19th century, Dinezon at times even outshadowed the three founding fathers because his books touched thousands of readers and were more widely sold. In fact, one of his novels sold more than 200,000 copies, an unheard of success in Yiddish literature. Dinezon achieved fame at the age of 20 with the publication of his first novel and remained famous until the day he died. He was so well known and beloved that every major figure of Yiddish literature came to his funeral in 1919.

Even encyclopedias in English recognized him. The early 20th-century Jewish Encyclopedia lists Dinezon as an important Yiddish writer (like other classical Yiddish writers, he also established a reputation as a Hebrew author), praise that is echoed in the contemporary Encyclopedia Judaica.

Sometimes mazel plays a role in literary fame but, in Dinezon’s case, it seemed to express itself in income and not in posthumous regard. And now that the worldwide Yiddish-reading community is vanishing, a writer’s lot can be determined by translation, which can bring fame, and to discovery, which in turn can prompt translation. If a writer doesn’t find his translator/editor in another language, he suffers the misfortune of neglect, which is what happened with Dinezon. If you ask any knowledgeable reader familiar with Aleichem and other famous Yiddish writers if he has ever heard of Dinezon, the answer would probably be no.

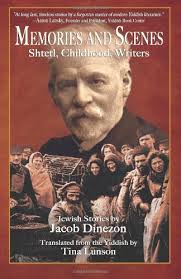

Until now, we have not had any work by Dinezon in English. But this lacuna has been successfully filled with the wonderful book of 11 Dinezon stories, beautifully translated by Tina Lunson and edited by Scott Davis, who has also provided an illuminating introduction: Memories and Scenes: Shtetl, Childhood, Writers (Jewish Storyteller Press, 2014).

Until now, we have not had any work by Dinezon in English. But this lacuna has been successfully filled with the wonderful book of 11 Dinezon stories, beautifully translated by Tina Lunson and edited by Scott Davis, who has also provided an illuminating introduction: Memories and Scenes: Shtetl, Childhood, Writers (Jewish Storyteller Press, 2014).

Dinezon was a social realist, accurately depicting small-town (shtetl) Jewish life. With a cinematic eye, he zeroes in on his characters, deftly telling fascinating stories while at the same time giving an accurate portrait of the mores, attitudes, speech and foibles of the men, women and children whom he depicts.

Like Dickens, Denizon wrote about the downtrodden and about poorly treated students in Hebrew schools with such realism that he actually brought about reforms. A cross section of Jewish society in Poland lives in his pages: the young and old, Chassidim and enlightened Jews, simple workingmen and rich householders. Every single one of his stories breathes with life and verisimilitude.

In this book of 11 stories, a collection published after Dinezon’s death in 1919, we have finely crafted tales – so in keeping with Jewish short-story writing at the turn of the 20th century – that recall vividly portrayed shtetl characters from Dinezon’s childhood years and memories of such literary figures as Mendele Mocher Sforim (Mendele the Bookseller, aka Sholem Abramovich), Peretz, and the playwright Avrom Goldfaden.

Dinezon also played an important historical role in the development of Yiddish as a literary language. In fact, he mentored, advised and befriended almost every major Jewish writer of his day. The list reads like a who’s who of late-19th- and early-20th-century modern Yiddish literature, including the writers mentioned above, as well as S. Ansky, David Frishman, Shimon Frug, Sholem Asch, David Pinski and Abraham Reisen.

In one of the superb stories, Mayer Yeke, we see how a boy’s great fear of the shtetl’s most righteous Jew, Mayer Yeke, turns to love and respect after he witnesses Mayer’s mitzvah assisting the town drunk. Sholem Yoyne Flask depicts a mild-mannered tailor transformed by the liquor in his flask into a fiery defender of the town’s poor folk – then something happens when a surprising discovery is made about his flask. With Motl Farber, Purimshpieler, we are introduced to a housepainter who languishes during the winter when he cannot work, but at Purim, he becomes the leader of a band of Purim players. When the troupe is arrested by the new Russian police chief, an unlikely “Esther” comes to their rescue.

A story that achieves the psychological depth of a Dostoevsky tale is Yosl Algebrenik and His Student. It tells the story of Yosl, an outstanding Talmud scholar, a genius some said, destined to become a great rabbi, who has a passion for mathematics. At age 30, for reasons no one remembers, he tosses away the Talmud and its commentaries for the study of algebra and algebraic logic. From then on, he spends all his time studying algebra, except for the few hours a week he devotes to tutoring children to eke out a living.

Another moving and profound story is called Borekh, after the name of the hero, a poor orphan living in the yeshivah. He doesn’t do well in talmudic studies but he has a talent for woodcarving, making dreidls, Purim groggers and toy animals for the children of the town. One day, he decides to leave the yeshivah and start anew, with hopes of making a great holy ark, “one that people have never seen before.” When he achieves that, he will send it to his friend in the yeshivah, who he knows will become a great scholar. He leaves without saying goodbye.

Some of Dinezon’s autobiographical sketches are as engaging as his fiction. In My First Work, he relates the childhood experience of reading his first Yiddish novel, a Jewish version of Robinson Crusoe. He is so taken by the book, he writes his own adventure story. In Sholem Yankev Abramovich, Dinezon tells how his debut novel, The Dark Young Man, was published and how he acquired his first copy in Moscow. At the same time, he learns that the Yiddish writer Mendele Mocher Sforim and the Hebrew author Sholem Abramovich are actually the same person.

It is not often that we are privileged to make a literary discovery of our own. With this book by Dinezon, the first in English, we happily encounter a master writer who deserves to be ranked with the great Yiddish writers whom he befriended and who admired him.

Curt Leviant’s most recent book is the short story collection Zix Zexy Ztories.