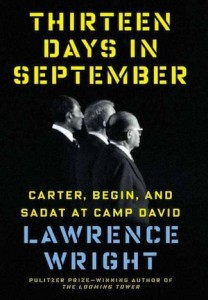

In September of 1978, U.S. president Jimmy Carter was at his wit’s end after 12 days of face-to-face negotiations between himself, Egyptian president Anwar Sadat and Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin.

Neither party was at all inclined to make peace, both had legitimate grievances with the other nation, advisors were telling them peace was not possible and that the leader and the nation each man represented could not be trusted. Things got so heated that all three parties had packed their bags and prepared statements that the talks had failed. Cars were idling in the Camp David driveway and Marine One, the presidential helicopter, was being readied to return Carter to Washington empty-handed.

Failure then, in the midst of the Cold War, would have meant an opening for the further arming of Egypt by the USSR and the nuclearization of the Middle East, where ultimately the fanatical forces that were then lurking in the shadows could very well force the Superpowers into a feared nuclear standoff. This was much like what was happening in East and West Germany at the time, only in the hot desert sands of the Middle East, it was far more likely that tempers would boil over.

These were the stakes at Camp David. The proposition was that Israel give back the Sinai Desert, land it had captured in the Six Day War, land that served as their saving buffer zone in the Yom Kippur War just five years earlier. Land that contained settlements of Israeli citizens that Begin had pledged on his life never to abandon. To do all of that in exchange for a piece of paper that promised peace, signed by three men who did not trust each other.

No one thought it probable or possible, not between these three men, Begin and Sadat, who had spent a lifetime fighting each other, and Carter, who lacked power at home and credibility abroad.

And, yet, they signed a lasting peace treaty. Israel had been at war with Egypt in one form or another for literally millennia, since the days of Pharaoh. They have not been at war since and, next to Jordan, Egypt is Israel’s closest ally in the region today.

Mark Twain said, “History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.” No two eras or events are the same, but many if not all have similarities.

Three years before Camp David, president Gerald Ford had announced that the United States would be reevaluating its relationship with Israel because of Israel’s power play, along with France, in the Suez Canal. A crisis, if you recall, that nearly, like the Cuban Missile Crisis, was only a series of missteps away from another nuclear confrontation between the United States and the USSR.

You could not have had Camp David if you had not also had the sobering realization of the Suez Canal Crisis. Carter could not have pressured Begin to do the good and hard thing for the future of Israel if Ford had not created enough daylight between the United States and Israel for Begin to see the light at the end of the endless wars with Egypt tunnel.

“History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.” I am neither a politician, nor a political scientist – though in truth I have a degree in the latter and every rabbi must ultimately learn the skills of the former. I am a student and teacher of history, the history of our people both in the land and yearning for the Land of Israel – and in all that has happened in these past many years, really since the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin (alav ha’shalom), I hear the rhyme of history.

Call it “darkest before the dawn,” but while I am filled with worry, the seriousness of the matter gives me hope that it can no longer be ignored or put off. That the pressure of absolutes that made Camp David possible has returned to make peace between the Israelis and Palestinians possible, though still improbable once again.

The region and its people are under near-bursting pressure. But pressure such as faces Israel also clarifies priorities. The greatest achievements of diplomacy have often come in the face of the most extreme pressure or, as Carl von Clausewitz wrote, “War is diplomacy by other means.”

Let’s examine the pressures in play.

In Israel, the status quo between Israelis and Palestinians is set to devolve into a third intifada. Meanwhile, there is a seismic schism between the Jews in Tel Aviv who voted overwhelmingly for the left and the Jews in Jerusalem who voted overwhelmingly for the right. Israelis on left and right are living two different realities, and they want two different futures for themselves and for the Palestinians.

In the Arab world, the forces of fundamentalism have shaken what little remains of the nation-states from their complacency with and tolerance for radicalization. Arab armies are mobilized against radicalism and terror. Yes, there is a vacuum of leadership throughout the Arab world, including among the Palestinians – but that also creates space for a leader to emerge.

Outside of the Middle East there is a fundamental disagreement between Western democracies that want Israel to act more like them, and Israel that wants the West to see that the terrorist threat confronting its democracy today is coming to their shores tomorrow. And for much of Europe tomorrow is today.

Jews are under attack around the globe. Antisemitism has come out of hiding once again. Much of antisemitism is ignorance and, yet, where do we find it? Most shockingly in our institutions of higher learning, where, in the most distorted and twisted forms, they equate Jews with Nazis. We see this happening particularly in the BDS campaigns that are sweeping across North American university campuses and right here at the University of British Columbia. These same antisemites defend terrorists as “heroes,” inviting them as speakers on campus. The Talmud says, “olam hafouch,” the world is upside down. Indeed, bigotry masquerades as fairness.

The pressure is not only external; it is internal, as well. The relationship between Jews in the Diaspora and Jews in Israel is becoming a dysfunctional marriage. It’s not headed for divorce but maybe separate bedrooms, as each tries to focus on things they love about the other, even when they are disappointed in the other.

It seems hopeless, I know, this election result whether you are left or right – the winner of the election was “hopelessness” itself. As Binyamin Netanyahu declared, in his view, there will never be a Palestinian state while he is prime minister. Those who voted for him believe that to be true and those who voted against him believe that to be true. That is the very definition of being without hope.

There is no solution to this conflict in this neighborhood, in this region, in this time. And, with no Palestinian leader who can do the same, it’s just not possible.

And, yet, we said the same before Camp David. We never thought Rabin would shake Arafat’s hand or make peace with Jordan. That Sharon, who built the settlements in Gaza would dismantle them, and that it didn’t lead to civil war.

Begin, Rabin, Sharon. These were not peace seekers, these were warriors, evolved Hawks.

We are not ready for another Camp David today; Netanyahu is not anywhere near ready, and there is no leader on the other side who can be a Sadat or a King Hussein of Jordan, a warrior who has the credibility to make peace.

By the same token, the only one in Israel right now who has the credibility to make peace with the Palestinians is Netanyahu. If he signs off on it, the people will believe it.

We are in a dark period and it may get darker. The pressure on Israel will only increase. The choices the country will have to make are impossible to understand right now. Our own solidarity both with Israel and with each other as fellow Jews will be tested, and there will be cracks. But that is nothing new for us, or for Israel. We don’t always agree, as Jews here or there, past or present, we seldom agree. In the end, however, what we have always done is survive. There’s the biggest improbability of all: that we are still here.

Israel is 67 years old. By comparison, it took the United States 150 years to reconcile slavery, a process that included a civil war, incomprehensible social disorder and civil unrest. And the United States, which is almost 200 years older than Israel, is still not yet resolved on the issue of race, as Ferguson – among many other events – reminds us.

Canada could say some of the same about true reconciliation with First Nations. We are not yet there.

This election was part of the growing pains of a nation and, in the age of nations, Israel is barely a teenager. Israel is the bat mitzvah girl who stands proudly, if not ironically, before the congregation and declares, “Today, I am a woman!” And we all smile and say to ourselves, “Not yet, but today you gave us a glimpse of the woman you will one day be. It would be more accurate to proclaim, “Today, I will no longer act like a child.”

“The arc of history is long,” Martin Luther King Jr. preached, “but it bends toward justice.” That’s the history of the world and it’s the story of our people, a story we are telling again around our seder tables this week.

What do you take away from the seder? That Pharaoh was cruel? That slavery was terrible? Yes, but also that we were redeemed; that the pressure on Pharaoh ultimately helped him see the light.

“La’yehudim hayta orah” we sang just recently on Purim and every week, as we end Shabbat with Havdalah. “The Jews enjoyed light and gladness, honor and joy. May we, too, experience these same blessings.” In another dark time, when all hope appeared lost, there was light. Let there be light once again!

Dan Moskovitz is senior rabbi of Temple Sholom in Vancouver.