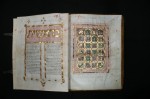

An illuminated Chumash from the El Escorial Library collection in Madrid. (photo from Courtesy of El Escorial Library)

Everyone has heard: “All good things must come to an end.” This saying certainly holds true when talking about Spanish Jewry’s Golden Age. Back in the Middle Ages, Spain’s church and state used forced conversion, expulsion and the Inquisition to obliterate Jewish life on their peninsula. While we might have some sense of how these methods devastated the lives of this once great Jewish community, we are probably less aware of the toll it took on the products of this culture, namely its books.

Let’s first be clear about what the Spanish Inquisition was. In her article “Medieval and Early Modern Sephardi Women,” published in the volume Jewish Women in Historical Perspective, Prof. Renée Levin Melamed writes that the Inquisition was “a temporary legal institution or court set up by the Roman Catholic Church in order to extirpate suspected heresy. Its jurisdiction was solely over baptized Catholics; thus, it could bring to trial converted Jews or Muslims, suspected witches, sectarians and the like.”

What set the Spanish Inquisition in motion? According to Prof. Felipe Fernandez-Armesto (author of Ferdinand and Isabella), in the late 1400s, the Spanish monarchs genuinely dreaded that the souls of their Catholic subjects would be forever lost to Islam and Judaism. Indeed, there was a pervasive fear that those who had already left Judaism (those former Jews known as conversos) had not really put aside their original religion. Hence, Spanish Christians strongly suspected conversos of Judaizing. To deal with this perceived threat to Christianity, the king and queen established the Inquisition.

Once the institution began functioning, religious considerations were perverted into accusations based upon economic rivalry, as well as the settling of assorted personal grudges. Moreover, as the offices of the Inquisition had the power to impound the possessions of the accused, it became advantageous to keep the institution going. Far worse than losing one’s possessions, however, was the sadistic physical torture the indicted commonly suffered, and the death by burning of those convicted. Fernandez-Armesto writes that contemporaries of Ferdinand and Isabella chose conveniently (and paradoxically) to forget – or ignore – the fact that “the Spanish royal house, too, was remotely affected by Jewish blood, through its founder, Henry of Trastámara, and his mother, Leonora de Guzmán, mistress of Alfonso XI.”

While Christian officials busied themselves in setting up the Inquisition, a few undaunted Spanish Jews moved ahead in printing sacred Hebrew texts. Significantly, these came to be highly regarded: “Their biblical texts were regarded as more accurate and authoritative … their codices are … very precise,” writes Teresa Ortega-Monasterio in Spanish Biblical Hebrew Manuscripts.

In Early Hebrew Printing in Sepharad ca. 1475–1497, Prof. Shimon Iakerson points out that “in 1482, Solomó ben Moisé Levi Alkabiz was established in Guadalajara and produced the first printed edition of the Talmud; in 1485, [Eliezer ben Abraham ibn] Alatansi was established in Híjar; and, in 1487, Samuel ben Mousa y Emanuel was working in Zamora (Torre Revello 17).”

While we know that Alkabiz printed a Rashi commentary on the Torah, information about Alatansi’s press is limited, and researchers only know of a fragment from the halachic compendium of Jacob ben Asher, including two copies of the latter prophets and two copies of the Torah. From what we know, ben Mousa, like Alkabiz, printed Rashi’s commentary on the Torah, as well.

It should be noted that during this same period, Hebrew printing was going on elsewhere, but it has been difficult to assign locations. Nevertheless, by comparing the fonts and printing paper to known texts, it is possible to suggest (but not confirm) those who may have worked on the books and the possible location of their workplace.

Intriguingly, for a limited time, there was cooperation between Jewish and non-Jewish printers. For example, it appears that Alfonso Fernandez de Cordoba “rented out” his frames to Jewish printers in Híjar in order that they might decorate the pages of their editions. Elsewhere, the Christian type caster Maestro Pedro of Guadalajar was mentioned in a Hebrew text.

Still, the Spanish monarchy felt threatened by the accessibility to Jewish learning afforded by the printing of Hebrew texts. Copies of the Talmud became a target of the Inquisition. From there, the hunt intensified, turning towards other Jewish texts. Two years before the 1492 expulsion of Jews from Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella ordered Grand Inquisitor Fray Tomás de Torquemada to burn Hebrew books. Later, during an auto-da-fé (act of faith, which really meant the public burning of a heretic) extravaganza in Salamanca, this same church father oversaw the burning of more than 6,000 volumes, which were said to be “infected with Jewish errors.”

Even after the expulsion, this ruthlessness continued, as Inquisition officials confiscated Jewish books and searched for any so-called “Jewish contamination” in the conversos community. Arias Montano (1527-1598), the first director of El Escorial Library, described the situation this way: “Of Hebrew books, of which there was great wealth in Spain, there is now great poverty.” In fact, the Inquisition finished off Hebrew printing in Spain.

Miraculously, some Hebrew books printed in Spain survived this onslaught, often as single copies or as mere fragments, writes Iakerson. Some of these remnants exists in Spain, stored in places like the library of the Royal Monastery of El Escorial, in the library of the Royal Palace of Madrid and in the library of the Complutense University of Madrid. While the originals remain out of the public eye, some facsimiles are on view today. For example, in Cabinet 43 of the Escorial Library’s viewing room, there is a facsimile of a 15th-century Torah, which also contains the Masora, or Masoretic texts (various scholarly notes on the biblical text written into the margins).

In his 1969 book Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts, art scholar Bezalel Narkiss located illustrated medieval Spanish Jewish manuscripts in several European libraries and museums. These beautiful texts are now housed in places such as Sarajevo’s National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, National Library of Portugal in Lisbon, the Oriental Department of the Berlin State Library, British Museum in London, Israel Museum in Jerusalem, National Library of Israel in Jerusalem, Oriental Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest and John Rylands University Library at the University of Manchester. Many of these collections are available for online viewing. For example, in 2012, the National Library of Spain gathered and mounted a large temporary exhibit of Spain’s most important medieval Hebrew texts. The exhibit is now viewable online and includes Hebrew Bibles, liturgical texts, texts dealing with reason and revelation, biblical exegesis, polemics and Spanish reports on the Inquisition trials of various conversos, suspected of Judaizing.

With the ability to digitize ancient documents and with the increasing international connection between libraries, perhaps additional surviving medieval Spanish Hebrew texts will be discovered. At the very least, we hope to learn more about those already discovered fragments of this once-flourishing Jewish culture.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic (take-a-peek-inside.com).