|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

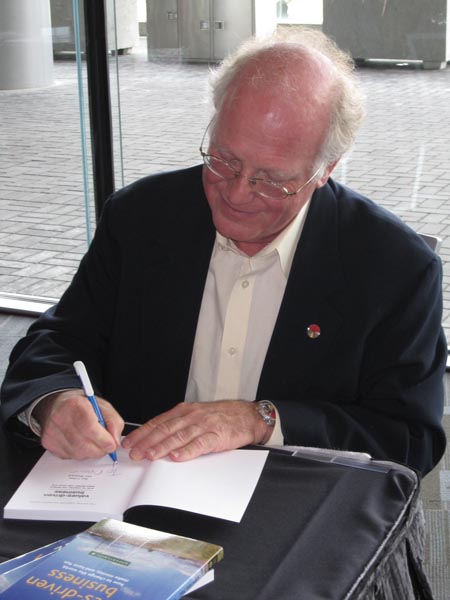

March 25, 2011 Ben & Jerry’s as role modelCYNTHIA RAMSAYIn helping others, we inevitably help ourselves. This is as true for businesses as it is for individuals, according to Ben Cohen, who, with Jerry Greenfield, founded Ben & Jerry’s ice cream company more than 30 years ago.

Cohen was in Vancouver to speak at this year’s Jewish Family Service Agency Innovators Lunch, which was held on March 16 at the Vancouver Convention Centre. Dawn Chubai, co-host of Citytv’s Breakfast Television, emceed the event, JFSA chair Diane Friedman welcomed the approximately 650 guests and JFSA executive director Joel Kaplan introduced the video that highlighted the agency’s seniors services (which can be seen at jfsa.ca). Since Pollock Clinics presented the luncheon, Neil Pollock introduced Cohen. “I think true innovators can naturally see a way to bring together novel combinations in harmony,” said Pollock. “Ben Cohen and his longtime business partner and friend Jerry Greenfield did just that, not only in the creation of their renowned original ice creams, but, as well, by showing the world that you can blend strong social values into the daily operations of a growing business and, by doing so, create a more viable and successful business, while carrying out what we refer to in Judaism as tikkun olam, which is helping to repair the world around us, which is a core Jewish value.” When Cohen took the podium, he explained that he and Greenfield met in a junior high gym class: “We were the two slowest, fattest kids in the class and there’d be the whole class running around the track and, half a lap behind, there’d be me and Jerry. And the coach would yell out, ‘Gentlemen, you have to run the mile in under 10 minutes! If don’t run it in under 10 minutes, you’re going to have to run it again!’ And Jerry would yell out, ‘But coach, if we don’t run it in under 10 minutes the first time, we’re certainly not going to run it in under 10 minutes the second time!’ That’s how I knew I wanted to be good friends with this guy.” Cohen shared how he dropped out of several post-secondary educational institutions, then tried to earn a living by making and selling pottery, while Greenfield completed a four-year degree but then got rejected by every medical school to which he applied. “We met up with each other, looked at ourselves and said, ‘We’re two real failures, what are we gonna do? How are we gonna get by in the world?’ And we said, ‘Well, I guess we’re just going to have to start our own business.’ Since the only thing we really liked doing was eating, we figured it should be a food business and our plan was to start a restaurant.” However, said Cohen, a friend warned them that restaurants go out of business all the time, but, if they really wanted to open one, they should make it a very limited menu. Since they wanted to live in a rural college town, explained Cohen, they thought they’d take a trend that was starting in the big cities and bring it to a smaller town, “and the two things that were happening at the time were bagels and homemade ice cream.” They chose the cheaper option, ice cream, even though they didn’t know how to make it. “So we found this big college textbook called Ice Cream and Jerry could understand it because he had this biochemistry background. And then we stumbled across this correspondence course in ice cream [out of] Penn State University,” which they took together and successfully completed. They initially considered warm locations for their first shop, but “all the warm rural college towns already had homemade ice cream parlors, so we decided to throw out the criteria of warm and ended up in Burlington, Vt., just south of the Canadian border, just south of Montreal.” Cohen explained that he and Greenfield each had $4,000 with which to start their business and, even though they had no credit history, were young (26 years old), unmarried, new to the area and had no collateral and or business experience, they managed to obtain a $4,000 bank loan. With that $12,000, they rented an abandoned gas station, bought used equipment from auctions, did all the renovations themselves and, in 1978, opened their first store. They broke even that year, but the winters proved very difficult financially. They began wholesaling ice creams, packaged in two-and-a-half gallon tubs, to restaurants, which Cohen delivered in his station wagon. “That actually worked, we got through that next winter and then the following winter came around, and I was selling more ice cream than we could fit in that insulated box and we finally got a real ice cream truck, except that it was an antique ... so all the money we were making on selling the ice cream we were losing on repairs to that vehicle, and we were going to go out of business. We were at the very end of our rope ... and finally, in a last-ditch effort to survive, we decided to pack our ice cream in pint containers so that we could sell it to the small mom-and-pop groceries that we were passing on the way to these restaurants. That kind of turned the corner for our business. From 50 accounts, we went to 250 accounts in a few months and then, once we had demonstrated that we could sell in small mom-and-pop groceries, the supermarkets started to carry it in Vermont and then, once we could show that it sold in Vermont, we could sell to independent ice cream distributors in neighboring states, in New Hampshire and Maine and New York, and things were starting to take off.” Then they were dropped by their Boston distributor because of pressure put on him by the Pillsbury Company, which had bought Häagen-Dazs. While legal remedies were possible, they didn’t have the financial resources. As well, they didn’t feel that a complaint to the Federal Trade Commission would achieve anything. Instead, they launched the What’s the Dough Boy Afraid Of? campaign, explained Cohen. Eventually, the negative publicity forced Pillsbury to relent. Cohen said that, at this point, he and Greenfield realized they were no longer ice cream men, but businessmen and “part of the economic machine that tends to oppress a lot of people and our first reaction was to sell the business.” A fellow restaurateur convinced Cohen to keep it, however, and run it on his own terms. So, when Cohen and Greenfield needed money to build an ice cream plant, instead of dealing with venture capitalists, they “decided to use this need for cash as an opportunity to make the community the owners of our business, so that, as the business grew, the community would automatically prosper because it ... would be owners. The way we found to do that was to hold what became the first-ever in-state Vermont public stock off. We sold stock of Ben & Jerry’s to our neighbors, Vermonters, people who had supported us from the very beginning.” One out of every hundred Vermont families became an owner, said Cohen. More success followed and, when the pair again needed money, they held a national public stock off and, as part of that initiative, they formalized the Ben & Jerry’s Foundation and the commitment that the foundation would get 7.5 percent of the pretax profits, “the highest amount of any publicly held company that gives to charity,” he said. The foundation was overwhelmed with requests and could only fund about five percent of the applications, Cohen continued. Therefore, he said, they put their minds to figuring out other ways in which their business could be of help, noting that business has become the most powerful force in the world, replacing the nation-state, which replaced religion before it. “What Jerry and I began to learn,” he explained, “is that there is a spiritual aspect to business, just as there is to the lives of individuals. As you give, you receive. As you help others, you are helped in return. As your business supports the community, the community supports your business. We’re all interconnected and, as we help others, we cannot avoid helping ourselves. Despite the fact that that is written in the Bible, it meets with incredible resistance in the business world.” In terms of their business, said Cohen, they decided to make choices that would affect positively both parts of the bottom line: profit and social concerns. He gave several examples, such as buying coffee from a co-op in New Mexico; naming a flavor after an at-risk area of the world so as to draw public attention to it, Rainforest Crunch, for instance; and making all their ingredients fair trade by 2013. “You know, in our books, what we conclude with is that, when business speaks, the public listens, the media listens, politicians listen, and we believe that it’s time for businesses and businesspeople to start taking responsibility, not just for their own narrow self-interest but for the common good, and there’s two ways to do it. The first is that business is an incredibly powerful force, which can integrate social concerns throughout its activities, and the second is supporting organizations like JFSA in its work to help people who are struggling to get food and medical care and to get through difficult periods in their lives. I think the especially powerful aspect of JFSA’s work is that it’s not just about handouts, but it’s about helping clients to self-advocate and to become self-reliant.”

|

|||||||||