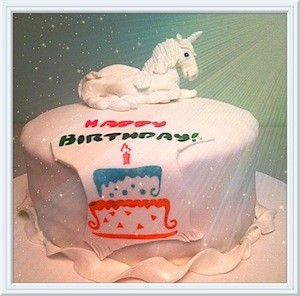

The author’s one photograph of her great-grandmother, Betty Brotman, “stiff-necked and corseted, with her dark hair combed tightly across her head.” (photo from Shula Klinger)

I have been researching my family history for many years, on and off. Much of my research has been online, using resources like JewishGen, the internet database of Jewish genealogical records. I have also found a home at Czernowitz-L, an email group hosted by Cornell University for people whose families come from what is now the Ukrainian city of Chernivtsi. Once known as “Jerusalem on the Prut,” Czernowitz – as it is still called by those who recall its Habsburg past – was once home to 50,000 Jews. Less than a third of this number survived the war.

Like many third-generation Czernowitzers, I write messages to Czernowitz-L in the hope that someone, somewhere, will remember hearing my family name and be able to point me in the direction of a lost relative. Very often, we hear nothing, but once in a blue moon, we strike gold.

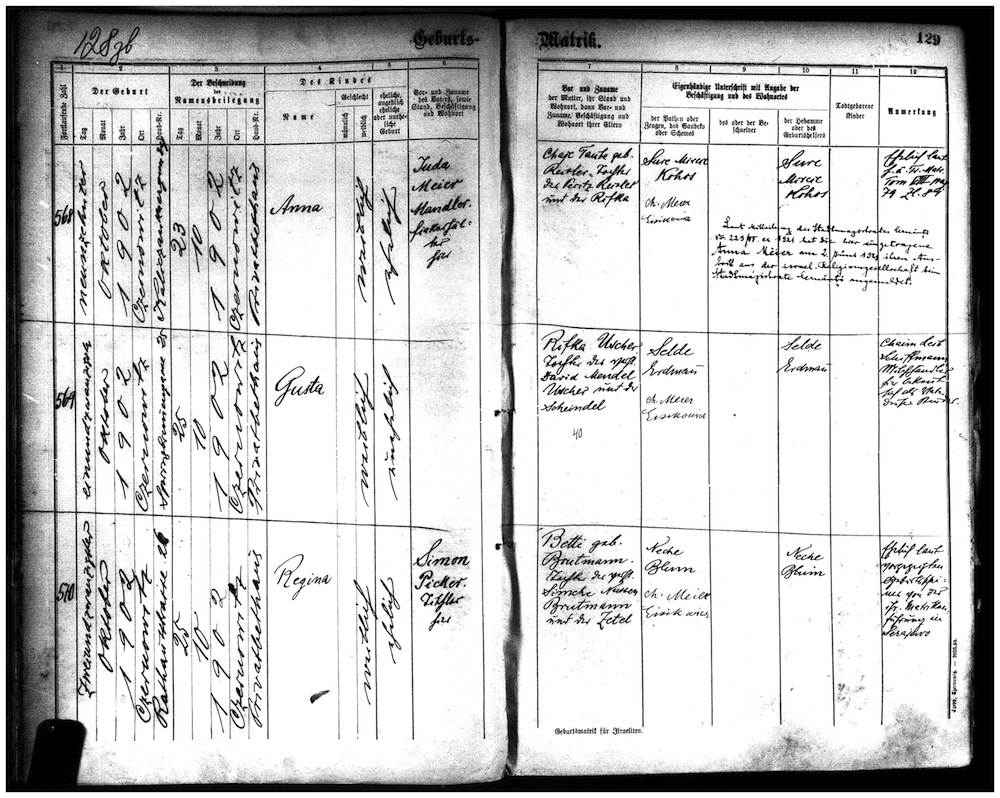

That’s what happened when I sent out an email asking list members if they knew of the family name Brotman. I had just received an image of my grandmother’s birth certificate from Czernowitz in 1902, which showed that Regina Picker’s mother, Betty, had been born a Brotman.

Shortly after I shared this information, I received an email from a lady in Portland, letting me know that she had married into the Brotman family in Oregon. She asked me if I would be interested in contacting one of her in-laws, whose mother had been a Brotman. He was very well-informed, she said. A conversation with him might yield some results. Not knowing that I lived here in Vancouver, she told me that Cyril Leonoff here. Naturally, I was thrilled and eager to talk to him as soon as I could.

Having corresponded with Cyril’s daughter, Anita, for awhile, we set a date and I drove over to meet them both. My children were very excited to find out if this man was a relative. I fielded the same question from them over and over again: “Are we 100% for sure, for sure related to him, Mommy? Or just 99%, do you think?”

On arriving at the Leonoff home, I was greeted by Anita. She showed us into the house, where a beautiful table had been set with fresh fruit and homemade poppy seed cake. Anita showed the children where to find some toy ships and I brought out my family photograph: my one photograph of my great-grandmother, Betty Brotman, stiff-necked and corseted, with her dark hair combed tightly across her head. Betty Brotman, who passed away at a young age, leaving her husband and children behind to survive the fall of the Habsburg Empire and the devastation of two world wars. But, back to the present.

Cyril asked me about the photo. I was eager to ask him a host of questions. Was I about to discover something extraordinary? Would I learn, after almost 20 years in Canada, that I had been living a few miles away from a relative, all this time? And after growing up in England, completely isolated from my extended family, was this man one of my elders? What did he know? What could he tell me? What did he remember of his people and their original home in Europe?

I watched his face as he calmly – and silently – looked at my photo. I tried to guess at what he was thinking. He suggested that we sit for tea before looking at his records upstairs. I accepted, glad of the tea, but thinking that this was a wonderful opportunity to practise mindfulness. Peace. Serenity in the face of burning curiosity and decades of longing for grandparents that I could talk to, family members who were able to tell me about their journeys, their struggles, their triumphs.

We sat quietly and poured tea while I tried not to boil over myself. We drank our tea and talked about the delicious poppy seed cake, which Anita’s daughter had made. And then Cyril asked me, “What are you looking for? What brings you here?”

His gaze was direct, his voice was polite. I told him the truth: I have no story, and I need one. My family was fractured, over and over, between Czernowitz, Cairo, Haifa and London. What little I do know of our history was told to me by an unreliable witness. A witness who had not wanted me, or anyone else, to find other, more reliable witnesses. A man who went to great lengths to separate his children from their story, or anyone that might refute his own accounts. A man who may have survived the war – and wars – physically, but who continued to fight their battles every day of his life, until he died. And, when he did die and I was finally able to say, rest in peace, it was truly the only peace he had ever had. He was traumatized, barely existing, unable to communicate or listen, to tell the whole truth or make any kind of authentic connection with another human being. My father, who I spent a lifetime trying to love, but who would never let me.

Cyril is 10 years older than my father was when he died. His intelligent gaze was steady and he listened quietly when I answered his questions. Difficult questions whose answers may well have been a lot longer than he had anticipated.

He didn’t respond directly, but we finished our tea slowly and he asked me up to his library. He said he had a book to show me. We climbed the stairs and entered a room with a high ceiling, filled with books. It reminded me of the shelves of my own family home, now gone. My father’s books.

Cyril walked over to a shelf by the window and removed a small volume of poetry. He opened it on a table and said, “I think you’ll want to see this.”

“This” was the inside cover of an old book inscribed in sepia copperplate. “Betty Brotman.”

“May I take a photograph of it?” I asked, after a few seconds, feeling a little superficial but not knowing where to put my happiness or my hands, other than on a camera.

“Yes,” said Cyril, so I did.

When the emotion had subsided and reason returned, I considered the facts: Cyril’s Betty may not be my great-grandmother, but still: there have been not one but three women named Betty in my family and the first was Betty Brotman. It isn’t impossible that his Brotmans were cousins to mine. It’s tenuous but, still, it’s a trace. A faint trace that proves we exist. That we left our mark on the world somewhere. That I am still connected to my people, even with my father’s concerted efforts to keep us all apart.

Cyril brought me to another room, where he kept his family records. He laid out a map showing where his family had come from. Indeed, our families were from nearby cities, again suggesting a possible link. He showed me his work on the history of Jewish farmers in Canada, where his branch of the Brotman family had homesteaded in 1889, and gave me some of his books to read. I thought about taking notes but was too moved to multitask. Simply sitting down with a man who might be a member of my family, who cared so deeply about his roots and was so proud of his family’s achievements, was overwhelming. He had done his own research and he had written it down – he had not hidden from it, or excised the story from memory. He is devoted to talking about and preserving it, just as I am.

And not only that, he wanted to talk to me, and he wanted to listen. To find out what I knew that might prove to be an irrefutable link between our families. He was curious; wanted names, dates, places.

“How old are you?” he asked me.

“Forty-four,” I replied, and cringed, feeling self-conscious. There was a pause.

“That old, eh?” he said, sounding shocked. Then he smiled – with his bright blue, 90-year-old eyes.

We looked around the room at framed photos and other artifacts of his family’s past. His record was abundant, both in photographs and documents. He pointed out a carved wooden picture frame that had been made by one of his relatives. I told him that my great-grandfather and my uncle were both carvers, that our family had worked in the lumber industry in Czernowitz. That our family had worked with trees for generations, in one way or another – whether as lumber, through sculpture or carpentry, or tree-planting in Israel in the 1940s. Another connection. Maybe.

When it was time to go, my older son asked me again. “Is he a relation? Is he ours?” I told him, “Very possibly.” And, again, he wanted to know the percentage probability. “Ninety-nine percent, then,” Benjamin decided.

It was hard to leave. After so many years, I wanted to stay until I dealt with that niggling one percent of doubt. I wanted to be sure. I had to know.

I don’t know how much of Cyril’s story is really my story, which he has taken such pains to write down. I don’t know if his Betty knew my Betty, if they were cousins, second cousins, or even more remotely related than that – or not at all. And I may never find out.

But, then again, even if we are just an appendix to his main narrative, I had a chance to read between the lines. To meet the Leonoffs, to eat with them and to ask questions about our fractured family stories. Because what matters is that we tried to knit those fractures together, to heal the tremendous wounds created by the past and the efforts made by those who refused – or were unable – to heal them on their own.

Months later, my children still talk about “our 99% relative.” They are proud to have an elder in Vancouver and they mention Cyril regularly. I love to hear them talk about him with affection and respect.

When it comes to family, I have discovered that 8- and 4-year-olds aren’t too worried about evidence. They really don’t care about that missing one percent. And now, as my children are also my teachers, neither do I.

Shula Klinger is an author, illustrator and journalist living in North Vancouver. This article is written with grateful thanks to Anita and Cyril Leonoff.