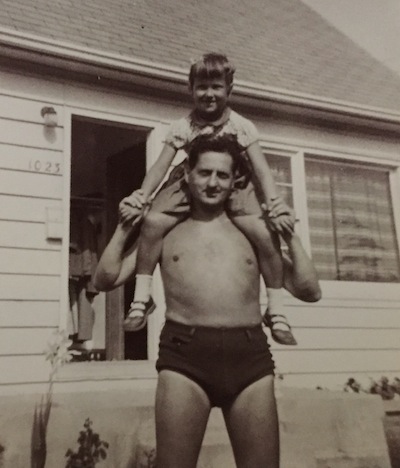

Selina Robinson, current MLA and NDP candidate for Coquitlam-Maillardville. (photo from Selina Robinson)

Coquitlam is not known as a hotbed of Jewish life, yet Selina Robinson notes that the area has been represented by three Jewish members of the legislature over the past few decades.

Riding boundaries frequently change, but the area was represented by Dave Barrett, when he was premier of the province, later by Norm Levi and, since 2013, by Robinson, in the riding now called Coquitlam-Maillardville. She appeared initially to lose last time around, but won by 41 votes in a recount. She’s not counting on a landslide this time, she said – she’ll be happy just to win on election night.

Robinson’s roots run deep in the Jewish community. Moving from Montreal to Richmond as a teen (she was Selina Dardick then), she remembers standing in the school hallway with a boy in a turban – two non-Christians excused every morning while their classmates recited the Lord’s Prayer. After high school, she went to Israel for a year, where she did an ulpan and Livnot U’Lehibanot, a program exploring Israel and Jewish heritage through hiking, community service, seminars and interactions with Israelis.

Returning to British Columbia, she was an administrator for Habonim Camp Miriam and later ran Lubavitch’s Camp Gan Israel. Meanwhile, she was studying at Simon Fraser University, obtaining a master’s degree and beginning a career in family therapy. She was headhunted to become director of counseling at the Jewish Family Service Agency and later served as associate executive director there. Her political career began on Coquitlam city council. In the legislature, she has been the New Democratic Party spokesperson for local government, sports and seniors.

She understands issues of affordability, she said, because she and her husband were on the Jewish cutting-edge putting down stakes in Coquitlam when they married 30 years ago. Part of the solution to affordability, she said, is providing more diversity of housing. Now that her kids are grown, they do not require the single-family suburban family home and could free it up for a larger family. They want to stay in the neighbourhood, where they are longtime active members of the Burquest Jewish community, but there are no townhouses or other appropriate options for them.

Different kinds of housing, such as the co-op model that is more secure than rental and not as expensive as individual homeownership, could improve the situation, she said. “We need to look at purpose-built rental and how to influence and encourage market-built rental.”

Affordable, accessible daycare in the province is also a pillar of affordability, according to Robinson, who calls daycare expenses “another mortgage payment every month.”

Another issue where Robinson has a personal perspective is her party’s promise to reinstate the B.C. Human Rights Commission, which the B.C. Liberals disbanded more than a decade ago.

“It speaks volumes that we take this seriously and there is a place for you to go to if you believe you’ve been discriminated against,” Robinson said. She was a surrogate mother for a friend’s baby and, in 2001, went to the Human Rights Commission over the legal definition of who was the baby’s mother.

“I had to register the birth under my name as the mother,” she said, even though she was not genetically related, as the baby she carried was conceived from the mother’s egg and the father’s sperm.

“Fatherhood is determined based on genetics but motherhood is based on from whom the baby was ‘expelled or extracted.’ That’s discriminatory. It should be based on genetics. So we took the government to court and the Human Rights Commission accepted the claim and then the government caved.”

Without the commission, someone who feels discriminated against would be required to go to court at their own expense, she said.

Robinson commends the provincial government for providing $100,000 to the Jewish community for increased security, and she recently signed a letter of support for a mosque in her area that is also seeking security funding.

“I think we have to address immediate risk,” she said. “But I think there’s a lot of work for us to do around making sure that people understand that this isn’t tolerated and to challenge discriminatory practices that do exist.”

Cuts to education over the past 16 years, she said, have led to reductions in things that might be considered “extras,” like taking opportunities to explore other cultures. Combined with these reductions, there are more families in which both parents are working, so few can get involved in providing extracurricular activities, as Robinson did when her kids were young, inviting classes to their sukkah and visiting to discuss Jewish topics with their public school classes.

“Those are the things that went by the wayside,” she said. “It allows for ‘others’ to be unfamiliar and, therefore, to be not trusted. And, therefore, hate can grow because of that gap.”

As NDP spokesperson for seniors, Robinson visits facilities and appreciates the role ethnocultural communities play in the delivery of social services.

“The fact that we have the Louis Brier and that it’s so established, and the Weinberg [Residence] … it’s so important,” she said, “for this community and not all communities have that.… I think government should support that, in helping ethnic groups make sure that their seniors have the comforts that they need and they can live their lives as the people that they are and how they’ve lived their entire lives.”

On the movement to boycott, divest from and sanction Israel, Robinson said she has “real problems with it.”

“My understanding of the BDS movement is to destroy the state of Israel,” she said. “I think that’s not OK. I support the state of Israel. I think the idea of not having a state of Israel is destructive and I do think that’s antisemitic.”

While she opposes BDS, she emphasized that people are free to make choices about where they invest or spend, and she defended the right of people to criticize any government.

“I didn’t like what [Stephen] Harper was doing. It doesn’t make me anti-Canadian, it just makes me an engaged person, an engaged Jew who is paying attention to what’s going on in the world around me.”

As British Columbia addresses economic development issues, Robinson urges them to look to Israel.

“When people talk about resource development here in Canada, particularly here in British Columbia, and they say, ‘Well, what else would we do?’ I say, ‘Well, take a look at Israel.’ They have no resources except people and they invest in their people and their people are amazing.… I want to see British Columbia take parts of that model – yes, we have resources and we should develop them wisely – but we have people and, when we invest in people, anything and everything is possible, and I think Israel’s an excellent example of that. I think we have a lot to learn from Israel. I would like to see a lot more of that.”

As Jewish voters ponder their options for the May 9 election, Robinson insists the NDP is the natural choice.

“I think that, in our hearts, our Jewish hearts, in our kishkes, we are New Democrats,” she said. “Jewish values are New Democrat values.”