Alex Greenberg’s family experience drove his work for the Dallas Holocaust Museum. (photo from Alex Greenberg)

It was a winding road for Alex Greenberg to become head of animation at a leading creative technology firm in Vancouver.

Born in Moldova, Greenberg and his family made aliyah in 1990, when he was 11 years old. After a “pretty regular childhood” in Israel, high school graduation, military service and a bit of travel around the world, Greenberg settled down to study animation.

“Unfortunately, two months into school, the director of the school took the money and split,” he said. “My luck. All the money was gone, the money I got from my [military] service.”

He started looking for schools in Canada and the United States where he could continue his studies. He discovered the Art Institute of Vancouver and moved here, by himself, in 2003.

Fast-forward … Greenberg is immersed in immersive technology. As head of animation for ngx Interactive, he has his finger in many projects – including one that shares the testimonies of Holocaust survivors and which, of everything he has worked on, is closest to his heart.

Founded more than two decades ago in Vancouver, ngx’s 80 or so employees, according to the company’s website, help clients “reimagine what’s possible in physical and digital spaces.”

“We work with four main sectors,” said Greenberg.

The museum sector is a big one. The company took part in a major re-envisioning of the National Portrait Gallery in London, UK. It reopened last year featuring 41 multimedia exhibits, including an artificial intelligence-powered portrait experience, an animated projection wall featuring some of the gallery’s most stunning portraits, interactive touch screens, and documentary films produced by ngx.

The medical sector is another area and, if you have ever taken your kids or grandkids to BC Children’s Hospital, you may have seen the interactive aquarium ngx developed for the emergency room so that young patients and their families have something to take their minds off the stressful reasons for their visit.

A third area is themed attractions, which have engaged audiences in such diverse spaces as Vancouver’s Science World, SeaWorld Abu Dhabi, Jurassic World in Beijing and the Canada Pavilion at Expo 2020 in Dubai.

Their corporate and institutional work, another core area for ngx, includes an interpretive exhibition in the pharmaceutical sciences building at the University of British Columbia, where visitors explore the world of health, and a project for Roche Canada, in the Toronto area, where the global pharmaceutical company has an interactive space for employees to engage with the Roche brand story.

Other projects help visitors explore cultural institutions like the Citadel Heritage Centre in Halifax, Indigenous cultural storytelling at Wanuskewin Heritage Park in Saskatoon, and interpretive exhibits about nature at Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota.

Greenberg’s specific role in ngx projects is lighting and look development.

“When you are working on a project, there’s a certain style to it, lighting, a certain mood, something that will convey the story,” he said. “We don’t just create these experiences to make them look cool. There’s a lot of thought that is being put behind them, thinking about the colours and thinking about the movement and [in the case of the BC Children’s Hospital virtual aquarium] how kids are going to interact with it to help them relax.”

In his seven years with the company, one project stands out among the rest for Greenberg.

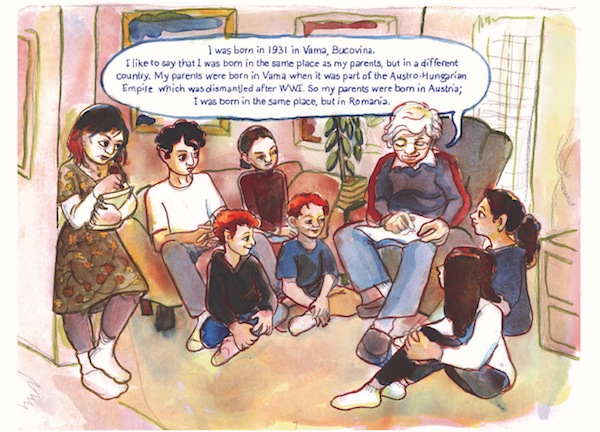

Visitors to the Dallas Holocaust Museum, in Texas, enter a room that transforms into a home in eastern Europe at the start of the Holocaust. Survivors share their testimonies as the home becomes no longer a refuge but a backdrop for the projection of scenes of atrocities. Then the screen rises and a holographic version of a survivor engages with the audience.

Hundreds of hours of interviews with survivors using 360-degree cameras allow for the realistic perspective of meeting these individuals in person. The project, called Dimensions in Testimony and developed in partnership with Steven Spielberg’s USC Shoah Foundation, introduces school groups and other museum visitors to a different survivor and their experiences each week of the year.

“This was one of the most impactful projects that I ever worked on,” Greenberg said. “You feel like you’re sitting in their living room. As you hear the story, the room begins to change. Lights going off, you hear marching of the boots outside, the rooms become slowly, almost unnoticeably dilapidated, just to show that the people were driven out of their homes and these homes are left with nothing but memories and a few photographs.

“After that introduction, the screen goes up and there’s a hologram production of that survivor. That’s the technology that the USC [Shoah] Foundation has developed. You can ask a question – for example, ‘What was your favourite sport when you were little?’ – and that would trigger a story where the survivor will be talking about where he used to play soccer with his friends when they were little.”

The project was close to home for Greenberg, whose grandfather lost his entire family in the Shoah.

“There was a big part of me in that experience,” said Greenberg. “I can tell and I can educate other people, people that are coming to this museum and people around the world that still don’t know what the Holocaust is, don’t know what a genocide is. It’s almost like I was telling my story.”