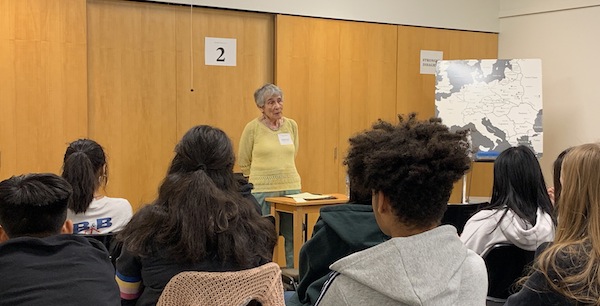

Simon Fraser University’s Prof. Lauren Faulkner Rossi, left, interviews child survivor Marie Doduck in a Zoom presentation Nov. 5. (screenshot)

For some survivors of the Holocaust, the COVID pandemic has brought back the traumas of the past. Marie Doduck spoke recently at a virtual event, recounting her survival story and her life in Canada, including her response to the initial lockdown in the spring. It is a response, she said, that is paralleled by many others in Vancouver’s group of child survivors of the Shoah.

Born in Brussels, the youngest of 11 children, Doduck spent most of her childhood hiding in orphanages, convents and strangers’ homes. In 2020, she found herself opening her front and back doors, reminding herself that she was free to go for a walk, yet haunted by the long-ago memory of hiding.

“It brought back a terrible time for us at the beginning of COVID,” she said during an interview that was webcast as part of Witnesses to History, a series presented by the Simon Fraser University department of history in partnership with the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre. “I know the other survivors feel the same way. I would say that was the hardest of all.”

When the war began, Doduck (then Mariette Rozen) was 4 years old. Her father died when she was a toddler and some of her older siblings were already married and had their own families. After the occupation of Belgium, those who remained at home set out on foot headed for Paris, where a sister lived, unaware that Paris, too, was under occupation. She remembers riding on the shoulders of her brother Henri and seeing what she thought was a magnificent sight.

“I saw this beautiful silver bird in the sky and I thought that was so beautiful,” Doduck recalled. It was surrounded by stars. “The next thing I know, I was flying into the ditch on the side of the road. Of course, the bird and those stars were planes diving and, even now, I can hear the whistle of the diving and the shooting. They were killing people on the road. That was my first contact with death and blood. It was all over the place.”

Soon, the family dispersed and Mariette began a years-long succession of shuttling between hiding places in various countries of northwestern Europe. A facility for languages began then and Doduck is now working on learning Mandarin, her 10th tongue.

In some homes where she was hidden, she would sit under the table while the family’s children did their homework. Then, after others had gone to bed, she scoured the homework to educate herself.

She also has something of a photographic memory and she realizes now that she served as a messenger, repeating what she had been told when asked by siblings who had joined the resistance and who could make occasional contact while she was in hiding.

As is the case with many survivors, Doduck has stories of almost-miraculous near-misses.

As is the case with many survivors, Doduck has stories of almost-miraculous near-misses.

While being hidden in a convent, she was exposed. The mother superior of the convent knew that Mariette was Jewish, but presumably most of the nuns did not. When one sister discovered her secret, she denounced the child to the Gestapo.

“Being a good nun, she went to the mother superior and told the mother superior what she had done,” Doduck recounted. “The mother superior had woken me up and taken me to the centre of the convent to the sewers and dumped me in the sewer. They came to the convent to search for me and they didn’t find me.”

In the sewer, filled with fetid water and rats, Mariette held her breath as she heard the boots of the Gestapo officers above her.

“I killed some rats to make a mountain so I didn’t have to stand in the cold water,” she said. “The mother superior saved me and that night I left and went to another place.”

Even more frighteningly, Mariette was rescued from a train almost certainly headed to catastrophe in the east.

“I was caught and I was put on a train,” she said. “I was the last one put on a cattle car and I was lucky because the cattle car had slats so I was able to breathe because they pushed us like sardines.… I remember the gate shouting and the clang, clang, clang, I can hear it now, and the lock.… Then the train stopped. I have no knowledge of places.”

The gate opened and Mariette saw a Gestapo officer.

“Black uniform, black hat, swastikas on his lapel, black boots, a leather strap with a revolver, a leather strap attached to a baton,” she recalled. “And, in German, he said, ‘What is my sister doing on this train?’ I looked left and I looked right. There was no other child but me.… This Gestapo that had probably killed hundreds of people, children as well probably, took me off the train, put me on his motorcycle and took me [away]. Years later, I found out that this Gestapo went to school with my brother Jean and used to come to my house on Friday to have dinner with us and he recognized me, that I was Jean’s sister.”

In the course of research for her memoir, Doduck recently discovered that her mother and one brother, Albert, were arrested and sent first to a transit camp and then on to Auschwitz. Her brother Jean, who was in the French resistance, was arrested elsewhere but was on the same train. Another brother, Simon, survived the war but died at Auschwitz in the weeks after liberation. Like thousands of others, he succumbed after well-intentioned Allied officials provided food to the starving inmates, whose stomachs could not assimilate it.

Including Doduck, eight siblings survived and somehow found one another after the war. One brother, Jule, chose to remain in Brussels with his family. Charles, who was also married before the war, moved to Brazil. Sister Sara went to the United States. Brother Bernard went to Palestine with Hashomer Hatzair, the socialist-Zionist youth movement.

Doduck, aged 12 at the time, and the three other siblings – Esther, Henri and Jack – were four of 1,123 Jewish child survivors of the Holocaust sponsored to come to Canada under the auspices of Canadian Jewish Congress in 1947.

Her recollections of arrival in her new homeland are not warm.

As the children disembarked the ship in Halifax, they found themselves in a compound surrounded by barbed wire, as though they would try to escape. From there, they were moved to a room with bars on the windows.

“I wasn’t called by my name,” she said. Each refugee had a number pinned to their chest. Hers was 73, she thinks, or possibly 74.

“Nobody talked to us,” she said. “Nobody really welcomed [us]. We were just a bunch of probably wild children. I can only describe that I had an adult’s mind in a child’s body. We survivors saw too much dirt, too much killing, too much that a child should ever see.

“We were treated like we were nothing at all,” she recalled.

She wanted to go to Vancouver. She had seen a map and knew that there were beaches there.

“I remember as a child we used to go to la plage, the beach, with the family,” she said. “That was happy times.

“And just like Brussels, it rains a lot too,” she added, laughing.

The four siblings were fostered by four different families in Vancouver. While not all the 1,123 children who were sponsored found loving homes, Doduck believes that she and her brother Jack were among the luckiest.

Doduck was taken in by a couple, Joseph and Minnie Satanov, who had no children and, weeks after Mariette arrived, celebrated their 30th wedding anniversary. The couple would become surrogate grandparents to Doduck’s three daughters and Doduck would care for them in their old age.

Still, the early months were difficult. The Satanovs spoke Yiddish, but it was a “highbrow” variation, Doduck said. Hers was “street Yiddish” and the initial communication was largely pointing and miming.

While her foster family was wonderful, Doduck, like some other survivor refugees, said their treatment by the broader Jewish community was inhospitable. Asked if the community welcomed her and her peers, she replied: “I hate to say it, they didn’t.”

As a child, she didn’t understand it. As an adult, especially now, as she plumbs her experiences in the process of writing her history, she thinks she understands and empathizes.

“The community did not accept us,” she said. “They were fearful. I understand this now. They were fearful of what we knew, of what we saw. As a child, I didn’t understand that. As an adult, I understand it today.”

Her process of assimilation is akin to a split personality, she explained. She encompasses both the child Mariette and the adult Marie.

“Survivors – this is a secret but I’ll tell the world today – survivors are two people. Mariette is the child who is still in me and is trying to come out, and Marie [is] the person I created to become a Canadian and to fit into our society here in Vancouver.”

“Mariette is a child from Europe. Marie is the name I took in Canada to hide who Mariette was,” said Doduck. “Survivors – this is a secret but I’ll tell the world today – survivors are two people. Mariette is the child who is still in me and is trying to come out, and Marie [is] the person I created to become a Canadian and to fit into our society here in Vancouver.”

That internal dichotomy is most evident when she speaks with school groups and others about her war-era experiences.

“When I do outreach speaking, I speak as Mariette,” she said. “When I leave the school, Mariette is put on a shelf and Marie takes over and becomes a Canadian. Marie cannot survive with the memories if I don’t put Mariette on the shelf…. I can’t live the memories. It takes a lot out of me to relive.”

The stories she has to share can be harrowing and there are still details that she is only now learning as she works on writing her memoirs. Lauren Faulkner Rossi, an assistant professor at SFU’s department of history interviewed her for the Nov. 5 event and is collaborating on the memoir.

While the pandemic may have jogged loose deep-seated memories, Doduck sees other alarming parallels in the world today that hearken to the dark past.

“We are again being persecuted, we are again being hated, we are again being hit, we are again being abused constantly,” she said of rising authoritarianism and antisemitism in parts of the world. “I see what I saw as a 4-year-old, 5-year-old. I’m seeing it around the world and nobody seems to see it, that the hate is coming again.”