The Ben-Gurion family in their Tel Aviv home, 1929. From left: David and Paula with youngest daughter Renana on Ben-Gurion’s lap, daughter Geula, father Avigdor Grün and son Amos. (photo from National Photo Collection of Israel / Government Press Office)

David Ben-Gurion, who died 50 years ago, insisted Israelis needed Hebrew names. The process was controversial – but the outcome is clear.

The 50th anniversary of the death of David Ben-Gurion will be marked Dec. 1. The first prime minister of Israel is generally remembered in noble terms, though we live in an era when heroes are being toppled from their plinths. His actions in times of war and peace have been parsed by historians – fairly and unfairly, as seems inevitable – but Ben-Gurion’s legacy among Zionists appears generally secure. Those with ideological axes to grind will grind, but the esteem in which most Israelis and overseas Jews view “the Old Man” remains largely favourable. However, an aspect of his policy that affected people in a very personal way has come in for a reconsideration in the past couple of decades, though it is hardly the stuff that will make or break a reputation. It is the Hebraization of names.

Ben-Gurion was a fierce advocate of Israelis (or, before 1948, Palestinian Jews) adopting names that reflect their new reality and that, by extension, turn their backs on the past and the diaspora. Ben-Gurion himself was born David Grün (or Gruen), changing his name to the Hebrew Ben-Gurion (son a lion cub) in 1910. By 1920, at the latest, he had become an evangelist for Hebraizing names and, when he was in power, he insisted that leading military and political figures adopt Hebrew names.

Ben-Gurion did not start this trend – though he is perhaps most closely associated with it because he was in a position to make it the force of law and custom. He instituted an administrative order that senior military figures and diplomatic officials representing Israel abroad must have Hebrew names. Others, like Golda Meir, he browbeat into the change.

Of course, Jews – and others – have been changing their names since the dawn of migration. People have frequently altered their names when moving to a new society, in order to fit in. Iberian Jews migrating en masse to the Low Countries after the expulsions of the 1490s are an early, well-documented example. Jews arriving on North American shores routinely changed their names, but so did non-Jewish migrants. It was not necessarily (or only) antisemitism that name-changers sought to outrun, but differentness in general. There are stories of French newcomers changing from Boisvert to Greenwood.

Dara Horn, in her book People Love Dead Jews, emphatically debunks the long-held belief passed down by generations that their family names had been changed at Ellis Island (or whatever entry point was appropriate to the story). No, she argues, that didn’t happen. The changing of names by Jewish new Canadians and Americans was, she contends, done by the migrants themselves and represents a sad realization that the Goldene Medina might not be the refuge from antisemitism they had hoped.

But changing one’s name to fit into a society already in progress, like America’s, was different than the situation of arriving in the pre-state Yishuv. This was not a matter of looking around for a local-sounding name and changing Moses to Murray or Lipschitz to Lipson. This required inventing a whole new lexicon of names. It was not the act of taking a common name in the new place, but of inventing entirely fresh first and last names.

The process was a legacy, ultimately, of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda (né Perlman), who was the driving force behind the revival of Hebrew as a vernacular language. After making aliyah in 1881, he came to believe that the redemption of both the people and the land of Israel required a new language to replace Yiddish. This represented a rejection of the diaspora reality and mentality, and served to create a medium through which an eventual (hoped-for) ingathering of exiles from around the world, including places where Yiddish was not the Jewish lingua franca, could communicate. The revival of an ancient land would coincide with the revival of an ancient language, both modernized to meet the needs of a new type of Jew. Ben-Yehuda raised his son and daughter exclusively in Hebrew, which must have made for a somewhat lonely childhood, being effectively the only two people in the world to speak the language as a mother tongue.

As the language spread – in large part thanks to Ben-Yehuda’s continued perseverance in promoting it and inventing modern words where the ancient language lacked them – the application of the new tongue to family and given names likewise grew.

The repudiation of the diaspora took on an entirely new relevance after the Holocaust. Some who made aliyah resisted changing their names, being attached, as is understandable, to one’s family name. Even so, no Jewish surnames were particularly long-established in the first place, since the practice of Jews adopting inheritable family names was only a century old, or a little more, at that time. The Austro-Hungarian Empire required Jews to take surnames in 1789 and in the Russian Empire and the German principalities not until the following century. At that time, choosing a name followed predictable patterns for Jews and non-Jews: a variation on “son of,” (Aronoff, son of Aron; Mendelsohn, son of Mendel), a reference to a profession (Becker for a baker; Melamed for a teacher), or a connection to the town or region (Frankel, from Franconia; Warshavski, from Warsaw; Wiener, from Vienna).

The adoption of Hebraized names in Palestine and Israel took four primary approaches.

The first was the traditional use of patronyms or matronyms, which is probably the oldest form of naming. Yiddish names, but also names that were German, Polish, Russian, English or French patronyms could be Hebraized: Davidson to Ben-David, Mendelson to Ben-Menachem, Simmons to Shimoni.

A second approach was to choose a Hebrew name that sounded like the original name. In some cases, the new name had a (sometimes remote) connotation with the original, as in the case of Lempel (little lamp) becoming Lapid (torch). Levi Shkolnik would become Israel’s third prime minister as Levi Eshkol. This was more than simply a near-homophone. It reflected another trend in the process, which was to adopt a name that spoke to the commitment of the chalutzim, the pioneers, whose Zionism was deeply informed by a back-to-the-land ethos. Eshkol means “cluster of fruit,” so it did double duty, sounding something like the original and also having a kinship with the blooming desert.

A third strategy was basic translation. Goldberg might become Har-Zahav (mountain of gold); Silver or Silverman might become Kaspi; Herbst, which in German and Yiddish means autumn, could be changed to a Hebrew equivalent, Stav or Stavi.

The fourth approach took the pioneer spirit and connection with the land to greater depths (with or without the homophonic advantage of Shkolnik/Eshkol). Flora, fauna and geography of the new homeland were attractive new names that situated the migrants linguistically and geographically. The writer Carrie-Anne Brownian cites such examples as Rotem (desert broom), Nitzan (flower bud), Yarden (Jordan), Alon (oak tree) and Tomer (palm tree). Simply adopting a place name gives us Hermoni, Eilat, Golani, Kineret and many others.

Those whose names already had a nature theme were at an advantage. The Haganah commander Moshe Klaynboym changed his family name, which meant “little tree” in Yiddish, to Sneh, Hebrew for “bush.”

Not necessarily related to nature, but to the idealization of the Zionist spirit, some took names like Amichai (my people live), Maor (light), Eyal (strength), Cherut (freedom) and Bat Or (daughter of light).

Golda Meyerson, after prodding from Ben-Gurion, became Golda Meir. Interestingly, her rather emphatically Yiddish given name she kept, presumably making Ben-Gurion half-satisfied.

As refugees from the Middle East and North Africa began pouring into Israel in the 1950s and ’60s, the Hebraization of names came to be seen as Ashkenormative, the taking of one’s ancestral name being another indignity (alongside inadequate housing and social stigmatization, among other things) that different-looking newcomers faced in their presumed Promised Land.

It seems, for example, that teachers encountering “strange” Mizrachi and Sephardi given names took it upon themselves, in some cases, to assign kids new names based not on any Zionist ideological imperative but for the same reason Canadian teachers in the early to mid-20th century dubbed kids with “foreign” names new ones the teachers could more easily pronounce. In retrospect, some have complained that this phenomenon was an insidious part of a larger (conscious, unconscious or some of both) effort to force Mizrahim and Sephardim to comport to Ashkenazi expectations even in things as intimate as a given name.

Sami Shalom Chetrit, a professor at Queens College in New York, who is of Moroccan-Israeli origin, recalled in a Forward article by Naomi Zeveloff, feeling outraged when an Israeli elementary school teacher nonchalantly renamed him, along with other non-Hebrew-named kids.

“Alif, your name from now on will be Aliza,” Chetrit recalled the teacher declaring. “Jackie, your name is Jacob, and Michele, your name is Michal. She kept going alphabetically. Then she said, ‘Sami, your name will be Shmuel Shalom.’

“I went to my father, crying.… I really felt like something was stolen from me, something precious. I said: ‘They changed my name! They changed it!’”

Chetrit’s father taught the teacher something the next day, according to the story. In Arabic, “Sami” comes from the root “samar,” the father said, meaning “heavenly superior,” and that, the father declared, is “international.”

The tendency eventually faded out. When a million migrants from the former Soviet Union arrived in Israel, after 1991, almost none chose to, or were pressured to, change their names.

There are contemporary exceptions even to this, though. Anatoly Shcharansky, one of the most famous of the Soviet “refuseniks,” became Natan Sharansky on arrival in Israel in 1986. The American historian Michael Bornstein became the Israeli politician-cum-diplomat Michael Oren, having changed his name when he made aliyah in 1979.

Newcomers to Israel today are free to change their names – and free to keep their “galut” (“exile”) names. Israel, today, is an overwhelmingly Hebrew society, though. New arrivals do not present a risk of swamping the place with Yiddish, Arabic, German, Polish or English, as might have seemed a danger 75 years ago, creating a Babel where cultural unity was desperately needed.

In addition to the psychological impacts of adopting Hebrew names (and language) as a refutation of the diaspora that had so recently been the locus of calamity, there was the practical reality of finding commonality among wildly diverse new citizens. That has been achieved. Even sorbing a million Russian-speaking new Israelis after 1990 did not dilute the ascendency of the Hebrew language. For whatever criticisms the forced (or vigorously encouraged) adoption of Hebrew names might invite, there is no doubt the intended outcome has been realized. Ben-Gurion’s dream not only of a Jewish state, but a Hebrew one, is firmly in place.

Glinert also traces the changes in the use of the language from biblical times through the Mishnah (before and after 200 CE), where the Hebrew of that period was more direct and seemingly more colloquial, as can be seen by comparing a text from the Mishnah with any chapter in the Bible. During the next two or three hundred years, written Hebrew then moved on from the Hebrew-only Mishnah to the two-language Talmud, with its mix of mostly Aramaic and much less Hebrew. (In all of this, of course, we only have written texts to go by.)

Glinert also traces the changes in the use of the language from biblical times through the Mishnah (before and after 200 CE), where the Hebrew of that period was more direct and seemingly more colloquial, as can be seen by comparing a text from the Mishnah with any chapter in the Bible. During the next two or three hundred years, written Hebrew then moved on from the Hebrew-only Mishnah to the two-language Talmud, with its mix of mostly Aramaic and much less Hebrew. (In all of this, of course, we only have written texts to go by.)

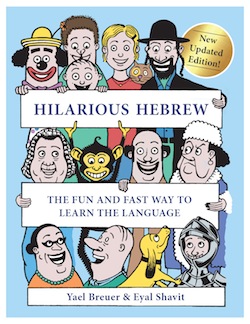

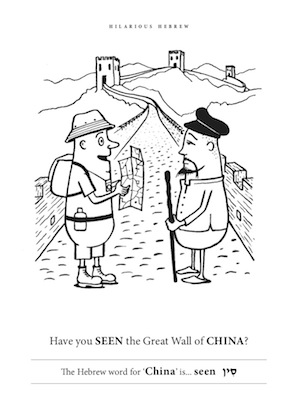

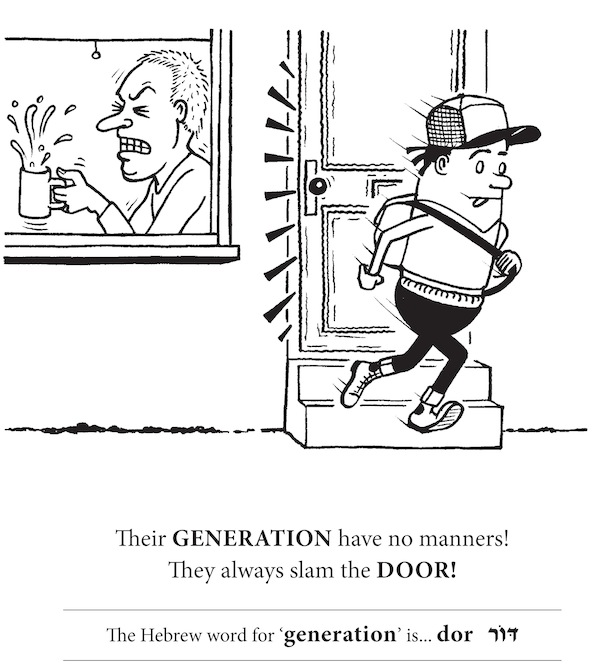

“The method in Hilarious Hebrew is aimed at teaching vocabulary rather than whole sentences because the whole point of it is to teach a Hebrew word in the context of a sentence in English that would convey the pronunciation and the meaning of the new word (in Hebrew) through a familiar, easy context (in English),” explained Hebrew teacher Yael Breuer, who co-authored the book with musician Eyal Shavit.

“The method in Hilarious Hebrew is aimed at teaching vocabulary rather than whole sentences because the whole point of it is to teach a Hebrew word in the context of a sentence in English that would convey the pronunciation and the meaning of the new word (in Hebrew) through a familiar, easy context (in English),” explained Hebrew teacher Yael Breuer, who co-authored the book with musician Eyal Shavit. In addition to teaching Modern Hebrew, Breuer writes for the Jewish Chronicle; she also has had her articles on British culture published in Israeli newspapers Haaretz and Maariv. From Rehovot, Breuer moved to Brighton 27 years ago, she said. “My husband, David, is English and, although he is originally from London, he already lived in Brighton when I met him.”

In addition to teaching Modern Hebrew, Breuer writes for the Jewish Chronicle; she also has had her articles on British culture published in Israeli newspapers Haaretz and Maariv. From Rehovot, Breuer moved to Brighton 27 years ago, she said. “My husband, David, is English and, although he is originally from London, he already lived in Brighton when I met him.”